Introduction

Isaiah is a living text in Africa. Some African nations find themselves in the Isaiah texts, which they relate to current political and cultural experiences. For example, Egyptian Christians read Isaiah 19—a chapter expressing both judgment and salvation for Egypt—into the experiences of the 2010s and the Arab Spring. Sudanese Christians read Isaiah 18—a chapter about the Cushites, “the people tall and smooth-skinned . . . whose land is divided by rivers,”—into the current experiences of suffering in South Sudan. And, of course, Ethiopian Christians, draw their tradition of reading Isaiah back to the New Testament narrative about the Ethiopian Eunuch (Acts 8:26–39, Isaiah 53:7–8).

Other African readers of Isaiah lack such explicit references to their ethnicity or political context, but they still experience Isaiah as a prophet who speaks the Word of God into their lives and concerns. On the one hand, Pentecostal and other charismatic churches experience the Spirit leading them to and through Isaiah texts, such as Isaiah 53, which reveals Jesus as the suffering servant of God, or Isaiah 55:10–11, which highlights the power of the Word of God. On the other hand, the historical churches with their fixed lectionaries encounter Isaiah texts regularly during Christmas (Isaiah 7:14, 9:2–7) and Easter (Isaiah 53:1–13), and in their Eucharistic liturgies many of them join the seraphim in Isaiah 6:3 and sing—in all vernacular languages—“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts.”

The following sections present useful introductory resources and provide a survey of examples of interaction between ‘Africa’ (the continent) and ‘Isaiah’ (the biblical book). Both are complex constructions. Reference to ‘Africa’ presupposes political and cartographic concepts and reference to ‘Isaiah’ presupposes historical and literary concepts. However, the survey will not go into questions about to what extent the authors whose works are presented can be labelled ‘African’ in some sense; the focus is on the theme of the works.

Introductory Resources

As a research topic, there has not been much focus on ‘Isaiah’—understood as the canonical book of Isaiah—in relation to Africa. Most researchers who have wanted to read Isaiah vis-à-vis African experiences and concerns have focused on certain texts or motifs in Isaiah, not the book as such. Nevertheless, a few introductory resources should be mentioned.

Holter, Knut. “Isaiah and Africa.” In New Studies in the Book of Isaiah: Essays in Honor of Hallvard Hagelia, edited by Markus P. Zehnder, 69–90. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2014. exporter

The article discusses examples of Africa in Isaiah (texts about Cush and Egypt, such as Isaiah 18 and 19) and Isaiah in Africa (academic interpretations of Isaiah, such as doctoral theses, journal articles, and Study Bibles).

Kitoko-Nsiku, Edouard. “Isaiah.” In Africa Bible Commentary, edited by Tokunboh Adeyemo, 835–78. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2006. exporter

The Isaiah section in the one-volume Africa Bible Commentary offers a chapter-by-chapter discussion that is informed by historical and Christian theological perspectives, but also relates many of the Isaiah texts and themes to various African experiences and concerns.

Nzimande, Makhosazana K. “Isaiah.” In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel’s Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page, 136–46. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010. exporter

Nzimande’s chapter is part of a collection of essays on “Israel’s Scriptures” (including the books of the Hebrew Bible and the Deuterocanonical and Pseudepigraphic Writings, but excluding the New Testament). Rather than provide a traditional chapter-by-chapter commentary, the authors pick texts and themes of their own liking and reflect on these from various African perspectives. Nzimande offers an example of postcolonial hermeneutics that allows current South African challenges of identity formation and gender to interpret Isaiah.

Zinkuratire, Victor. “Isaiah 1-39.” In Global Bible Commentary, edited by Daniel Patte, 186–94. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2004. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Zinkuratire, the General Editor of The African Bible (1999), provides the commentary on Isaiah 1–39 in the one-volume Global Bible Commentary. He draws connections between the history of Israel and Judah, pointing to parallels in African precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial history. He also notes other similarities, linked to key texts: Isaiah 5:1–24: moral and societal crimes; 5:25–30, 14:4b–23, 37:22b–29: devastation caused by wars; 2:2–5: future Jerusalem and the nations; 35: happy homecoming.

Key Studies

The two following examples are key studies in the sense that they represent a strong interpretive tradition of church and academia in Africa and beyond, concentrating on the Immanuel texts in Isaiah 7–11 and the Servant texts in Isaiah 42–53.

Ejeh, Theophilus U. The Servant of Yahweh in Isaiah 52:13-53:12: A Historical Critical and Afro-Cultural Hermeneutical Analysis with the Igalas of Nigeria in View. Zurich: LIT Verlag, 2012. exporter

The book attempts to build a bridge between Isaiah 52:13–53:12 and the life and culture of the Igala of Nigeria. After a historical-critical interpretation and a reading of the text in light of its New Testament reception, it is related to the language and worldview of the Igala.

Kahindo, Veronique. “Prince of Peace for the Kingdom of Judah in Crisis: A Contextual Reading of Isaiah 9:1-6 from the Perspective of Peace-Building Efforts in the Eastern Provinces of the DRC.” PhD diss., University of South Africa, 2016. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The dissertation analyses Isaiah 9:1–6, using a tri-polar exegetical model developed by Justin Ukpong. The text is read in dialogue with people in the eastern part of the DRC, who—like the Judean first readers of the text—yearn for a righteous, faithful, and legitimate Prince of Peace who is willing to put an end to the interminable violence they experience.

Bibliographies

“Africa and the Bible” is a quite new genre, with the first bibliographies dating back to the 1990s (Holter 1996, LeMarquand 2000 and Holter 2002). As for “Africa and Isaiah,” the first comprehensive bibliography is Holter et al. 2024, which formed the basis for this article.

Holter, Knut. Tropical Africa and the Old Testament: A Select and Annotated Bibliography. Olso: University of Oslo, 1996. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The first bibliography on published, scholarly texts that explicitly relate Africa and the Old Testament to each other. This annotated resource offers easy access to some of the main lines in scholarly work from the second half of the twentieth century, a period that includes the first and second generation of African Old Testament scholars. Of 232 entries, 11 are to Isaiah.

Holter, Knut. “An Annotated Bibliography of African Doctoral Dissertations in Old Testament Studies, 1967-2000.” In Old Testament Research for Africa: A Critical and Annotated Bibliography of African Old Testament Dissertations, 1967-2000, 20–60. New York: Peter Lang, 2002. URL: lien web accès: exporter

This book is a study of 89 doctoral theses by the first and second generation of African Old Testament scholars (1967 to 2000). Three are Isaiah studies (Akpunonu, Mbuwayesango, Yilpet), and five others let Isaiah texts play some role. Only the part containing the annotated bibliography is accessible online.

Holter, Knut, Samuel K. Bussey, Yoel Koster, and Grant LeMarquand. “Isaiah.” African Theology Worldwide, December 2024. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The first comprehensive bibliography on Africa and Isaiah. This resource, which includes both contextually sensitive and more traditional historical–critical studies, is searchable and regularly updated.

LeMarquand, Grant. “A Bibliography of the Bible in Africa.” In The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories, and Trends, edited by Gerald O. West and Musa W. Dube, 633–800. Leiden: Brill, 2000. URL: lien web accès: exporter

This bibliography—published in various versions around the turn of the century, including the document linked to here—is still a goldmine for research into biblical interpretation in Africa in the second half of the twentieth century, also with references to Isaiah studies. The material is categorized into broad topics.

Trimm, Charlie. “Works Written by Black Old Testament Scholars: Bibliography.” Biola University Faculty Articles and Research, December 2020. URL: lien web accès: exporter

An extensive list (170 pages) of scholarly works by Black (i.e., African and US) Old Testament scholars. The document is categorized by author and topic, the latter including each book of the Bible, with 11 entries on Isaiah.

Primary Resources Online

Digital platforms such as YouTube offer a large number of Bible studies, sermons, and other kinds of resources that show how Isaiah is read and referred to in political and religious discourses throughout the African continent. The following are some illustrative examples.

Adeboye, Enoch A. Signs and Wonders of the Spoken Word. Sermon video, 56:53. Recorded at the annual Holy Ghost Congress of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, Redemption Camp, Ogun State, Nigeria, 10-15 December, 2012. Posted 28 November, 2013. URL: lien web accès: exporter

A sermon by Pastor Enoch A. Adeboye, the General Overseer of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, a megachurch based in Nigeria but today present all over the world. The sermon starts in Isaiah 55:10–11 and emphasizes the power of the Word of God. For further discussion, see the subsection on ‘Preaching’ below.

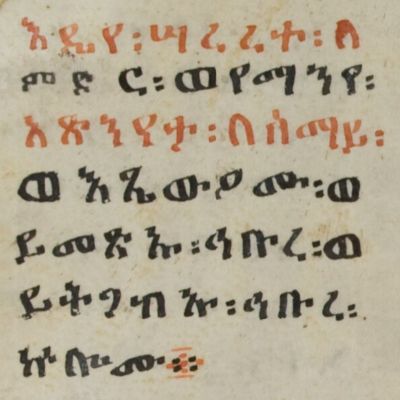

Endangered Archives Programme. “Isayiyas Andemta (the Commentary of the Book of Prophet Isaiyah) [20th Century].” British Library. Accessed January 9, 2024. URL: lien web accès: exporter

An Isaiah commentary that has been digitized as part of a British Museum project to conserve andemta manuscripts (in Geʽez and Amharic) of biblical and patristic commentaries. The andemta commentaries are made according to a lay exegetical tradition and the material of the present project includes 70–75 codices. For further discussion, see the subsection on ‘Ethiopia’ below.

Hawari, Alhadi. “‘Our Suffering Is Biblical Curse Not SPLM Making,’ Says Kuol.” Eye Radio, December 19, 2022. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The South Sudanese politician Kuol Manyang Juuk, a member of the SPLM (Sudan People’s Liberation Movement) argues that the SPLM should not be blamed for the current challenges South Sudan is facing (December 2022), rather these challenges reflect a prophetic biblical curse, found in Isaiah 18. For further discussion, see the subsection on ‘Sudan and South Sudan’ below.

Mbewe, Conrad. The Exaltation of Christ. Sermon audio, 41:32. Recorded at Kabwata Baptist Church, Lusaka, Zambia. Posted on 24 June, 1990. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Dr. Conrad Mbewe (PhD in Missiology from the University of Pretoria) has lead Kabwata Baptist Church (Lusaka, Zambia) since 1987 and has a global preaching ministry. The sermon linked to here is part of a series of sermons on Isaiah 52:13–53:12, reading the text as an eighth-century prophecy about Jesus.

Nweke, Josie. Isaiah’s Suffering Servant. Sermon video, 59:11. Recorded at Pentecostal Christian Faith Assembly, Bukuru, Jos South, Plateau State, Nigeria. Posted 5 September, 2015. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Pastor Josie Nweke is the Academic Dean of Students at Christian Faith Institute (Jos, Nigeria). The sermon linked to here reads the Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53 as a text about Jesus, who suffered for our sins and rose from the grave.

Randriatsifofo, Patrick. The Sanctus in the Malagasy Lutheran Church. Worship video, 10:53. Recorded in Ampitakely Lutheran Church, Fianarantsoa, Madagascar in 2018. Posted 4 November, 2024. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The Sanctus—the centre of the Eucharistic liturgy in most historical churches—lets the worshippers praise the holiness of God with the song of the seraphim in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord Almighty.” The video shows the Sanctus in a Eucharistic celebration of a parish church of the Malagasy Lutheran Church and illustrates some of the inculturation strategies of the church, rendering the song of the seraphim—“Masina, masina, masina, Zanahary Tomponai”—with a vocabulary based on traditional Malagasy religion and culture. For further discussion, see Holter 2017 in the subsection on ‘Translation, Contextualization and Liturgical Use’.

Restore the Path. Isaiah 19 Egypt prophecy being fulfilled. Worship video, 21:10. Recorded at the Cave Church in Cairo, Egypt on 11 November, 2011. Posted 7 September, 2016. URL: lien web accès: exporter

During the Arab Spring, after months of fighting and bloodshed, 70,000 Christians came together in the Cave Church in Cairo for a night vigil of worship and prayer. The video shows participants repeatedly shouting “Jeshua”, the Hebrew form of “Jesus”. This is seen as a fulfilment of Isaiah 19 and its reference to an altar for the Lord in the heart of Egypt (v. 19) and five Egyptian cities speaking the language of Canaan and swearing allegiance to the Lord Almighty (v. 18). For further discussion, see the subsection on ‘Egypt’ below.

Wel, David, and David Makuei. The Truth behind Isaiah 18, Prophesy and the Sufferings of People of South Sudan. Political analysis video, 1:41:18. Streamed live on 21 December, 2022. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The video discusses South Sudanese politician Kuol Manyang Juuk’s claim that the suffering of the South Sudanese is a divine punishment for the sins of the people, a punishment that is foretold in Isaiah 18.

Isaiah in Northeast Africa

Biblical interpretation in Egypt and Ethiopia differs from that of the rest of the continent in two ways. First, each of the two countries hosts Orthodox churches that trace their roots to the first centuries of the Christian era. In consequence, they have developed forms of biblical interpretation, liturgy, and praxis that differ from most other churches in Africa, both the Western-initiated ones and the African-initiated ones. Second, both churches emphasize that “we” are mentioned in the Bible, as “Egypt” and “Ethiopia” play crucial textual roles, both in Isaiah and in the Bible as a whole. Biblical interpretation in Sudan also has a long history, but largely disappeared after the collapse of the medieval Nubian kingdoms. In recent years, Christians in Sudan and South Sudan have begun to interpret Isaiah 18 in relation to their experiences of political conflict and war.

Egypt

The Coptic tradition emphasizes the New Testament narrative about the Holy Family finding refuge in Egypt (Matthew 2) but also some of the more than seven hundred references to “Egypt” in the Old Testament. A crucial example of the latter is Isaiah 19, a chapter addressing Egypt, first with judgment (vv. 1–17) and then with salvation (vv. 18–25), seeing the reference to “an altar to the Lord in the heart of Egypt” (v. 19) as a reference to the church. In the Coptic interpretation (and, more recently, in Egyptian Evangelical interpretation), experiences of oppression have been interpreted in light of vv. 1–17 whereas experiences of restoration have been interpreted in light of vv. 18–25. There have been frequent examples of such interpretations following the Arab Spring in 2011.

Angaelos. The Altar in the Midst of Egypt: A Brief Introduction to the Coptic Orthodox Church. Stevenage: Coptic Orthodox Church Centre, 2000. URL: lien web accès: exporter

A brief interpretation of the Coptic Orthodox Church as a fulfilment of the reference to an “altar to the Lord in the heart of Egypt” in Isaiah 19:19. This interpretive tradition goes back to St. Cyril the Great (376–444 AD), who argued that “The ‘altar’ which was established in the midst of the land of Egypt is the Christian Church which replaced the pagan temples as the idols collapsed and the temples became deserted in the presence of the Lord Jesus” (p. viii).

Balogh, Csaba. “The Stele of YHWH in Egypt: The Prophecies of Isaiah 18-20 Concerning Egypt and Kush.” PhD diss., Theologische Universiteit Kampen, 2009. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The thesis is a valuable study of Isaiah 18–20, part of a collection of prophecies about the nations (Isaiah 13–23). Later published as The Stele of YHWH in Egypt: The Prophecies of Isaiah 18-20 Concerning Egypt and Kush. Oudtestamentische Studiën 60. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Holter, Knut. “To the Question of an Ethics of Bible Translation: Some Reflections in Relation to Septuagint Isaiah 6:1 and 19:25.” Old Testament Essays 31, no. 3 (2018): 650–61. URL: lien web accès: exporter

A discussion of two texts from Septuagint Isaiah in dialogue with some concerns of recent discourses of Bible translation ethics. The main focus is on the question of a translation’s “loyalty” vis–à–vis source text, target language and culture, and other actors involved in the translation process. The article argues that the two case texts from Septuagint Isaiah offer different solutions; whereas 6:1 accentuates a concept already present in the Hebrew text, 19:25 offers a competing narrative to that of the Hebrew text.

LeMarquand, Grant. “‘Blessed Be My People Egypt’: Isaiah 19–20 with Special Reference to Reception by the Coptic Church in Egypt.” In Context Matters: Old Testament Essays from Africa and Beyond Honoring Knut Holter, edited by Madipoane Masenya Masenya, Marta Høyland Lavik, Ntozakhe Simon Cezula, and Tina Dykesteen Nilsen, 51–62. International Voices in Biblical Studies 16. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2023. URL: lien web accès: exporter

In the Old Testament, Egypt is not only spoken of as a place of bondage, but also a place of refuge for those escaping famine or war. Isaiah 19 expresses a great eschatological hope that Egypt will become part of God’s covenant with the nations. Furthermore, drawing on Matthew 2, the Coptic Orthodox Church shows that Egypt was the place of refuge for the Son of God himself and views it as a type of Gentile inclusion. Freely accessible for most users in the Global South.

Marzouk, Safwat. “An Egyptian Theology.” In Emerging Theologies from the Global South, edited by Mitri Raheb and Mark A. Lamport, 286–301. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2023. exporter

Egyptian Christians saw the political turmoil during the Arab Spring as reflecting the words of judgment in the first half of Isaiah 19, whereas they saw the toppling of the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013 as a divine response reflecting the words of salvation in the second half of the chapter. In response, the article discusses Isaiah 19 from exegetical and hermeneutical perspectives, challenging Egyptian Christians who celebrate the inclusion of Egypt in God’s plan of salvation to ask themselves how they can include the marginalized and oppressed.

Ethiopia

According to Kebra Nagast, the national epic of Ethiopia, the Ethiopian dynasty—of which Haile Selassie (1892–1975) was the last emperor—goes back to the meeting between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10) with their son, Menelik, as the first emperor. This tradition is related to a strong focus on the Old Testament in Ethiopian Orthodox theology and church life. The translators of the Septuagint (in the third to first centuries BCE) rendered the 50–60 Old Testament references to Cush or Cushim—a people living along the Nile, south of Egypt—with Aithiopía or Aithíopes, thus establishing a strong translative tradition of seeing ‘Ethiopia’ in the biblical texts. Amongst the Isaiah references to Cush (18:1, 20:3–4, 37:9, 43:3, 45:14), the most influential is 18:1 which throughout the chapter is developed into a portrayal of Cushites worshipping Yahweh in Jerusalem (cf. Psalms 68:32; v. 31 in English translations).

An, Keon-Sang. An Ethiopian Reading of the Bible: Biblical Interpretation of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2015. exporter

A chapter on biblical interpretation in the preaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (EOTC) includes a presentation and analysis of a sermon on Isaiah 53:8. The sermon has two foci; it reads Isaiah 53 as a prophecy of Christ and it points out that it was Isaiah 53 that led the Ethiopian Eunuch in Acts 8 to conversion and baptism.

Cowley, Roger W. “Old Testament Introduction in the Andemta Commentary Tradition.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 12, no. 1 (1974): 133–75. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The andemta commentary tradition of the EOTC includes translation and commentary in Amharic on the Bible and related literature written in Geʽez. In this tradition, each biblical book is given an introduction that includes the writer’s name and its meaning, the significance of and reason for this name, matters of the content presented by the writer, matters of doctrine revealed to the writer and the canonical authority of his writing. The article provides the first annotated translation of the introduction to Isaiah in the andemta tradition (pp. 157–159).

Ježek, Václav. “Ethiopian Exegetical Traditions and Exegetical Imagination Viewed in the Context of Byzantine Orthodoxy.” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 78, no. 1 (December 20, 2022): 12. DOI: 10.4102/hts.v78i1.7997 URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article argues that “the importance and originality of Ethiopian exegesis can perhaps appear only if one compares it to other traditions, such as the Byzantine or post-Byzantine Orthodox exegetical tradition” (p. 11). One example is an explanation of Isaiah 40:31—those who hope in the Lord . . . will soar on wings like eagles—which illustrates how the Ethiopian exegetical tradition manages to maintain a highly contextual and lively relationship with the community and contemporary issues, as well as with other traditions.

Ullendorff, Edward. Ethiopia and the Bible. London: Oxford University Press, 1968. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Ullendorff’s study is the classic introduction to the interface of Ethiopia (Cush) and the Bible. It includes a few references to Isaiah, partly referring to geographical and topographical entities (Isaiah 18:2), partly to Jewish diaspora centres (Isaiah 11:11), partly to the wealth of Cush (45:14), and partly to the Ethiopian eunuch who reads Isaiah 53 (Acts 8:32–33).

Unseth, Peter. “Hebrew Kush: Sudan, Ethiopia, or Where?” Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology 18, no. 2 (1999): 143–59. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The Septuagint—and most subsequent translations—rendered the Hebrew geographical reference Cush as ‘Ethiopia’, but in recent years other suggestions have been made, such as ‘Sudan’, ‘Africa’, or it has simply been transliterated as ‘Cush’. The article argues that the Old Testament references to Cush do not refer specifically or exclusively to modern states like Ethiopia or Sudan.

Sudan and South Sudan

The Old Testament includes approximately fifty references to Cush, a geographical entity that is situated along the River Nile, south of Egypt. Eight of these references are found in Isaiah, of which particularly Isaiah 18:1–7 draws a vivid picture of the Cushites. The Septuagint used the Greek term Aithiopía (“dark face”, used generally about people of dark skin) to render Cush and this rendering has been influential throughout the history of Bible translation. In recent years, some translations have rendered the Hebrew term Cush as ‘Sudan’, the Arabic equivalent of the Greek term Aithiopía (cf. bilād as-sūdān, “the land of the blacks”); others have suggested rendering it as ‘Africa’ (“the continent of the blacks”). Historically, the rendering of Cush as ‘Ethiopia’ has played an immense role in Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (see above). More recently the rendering as ‘Sudan’ has also played various roles in religious identification and theological interpretation amongst Sudanese Christians.

Dau, Isaiah M. “Suffering and God: A Theological-Ethical Study of the War in the Sudan, 1955-.” PhD diss., Stellenbosch University, 2000. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The thesis examines historical, political, socio-economic and religious factors behind one of the longest wars in Africa. For several decades, the predominantly Muslim north fought against the Christian and traditionalist south. Some attention is given to the interpretation of Isaiah 18 among the Bor Dinka community (pp. 55–58). Later published as Suffering and God: A Theological Reflection on the War in Sudan. Faith in Sudan 13. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 2003.

LeMarquand, Grant. “Bibles, Crosses, Songs, Guns and Oil: Sudanese ‘Readings’ of the Bible in the Midst of Civil War.” Anglican and Episcopal History 75, no. 4 (2006): 553–79. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Sudanese theology is mostly found at an oral level, in sermons, songs, and prayers. Isaiah 18 is often mentioned because of its description of a land divided by rivers and a people tall and smooth-skinned, which is interpreted as referring to the geography and peoples of Sudan. Furthermore, the war metaphors are understood as referring to the civil war in Sudan, but there is hope as well, in turning to the Lord Almighty and bringing gifts to Mount Zion (v. 7).

Nikkel, Marc R. “The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan: With Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 1994. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The thesis documents the development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan both during and since the missionary era, using songs of Dinka Christians as a major source. “Of widespread interest to Dinka Christians are the Biblical passages which speak of Sudan. The prophecy against Cush in Isaiah 18, has frequently been interpreted in sermons as a prediction of post–independence civil war in Sudan” (p. 31). For example, the song “The Pipeline” (1989), says that “War was prophesied by Isaiah, and so it has come among us” (p. 274). Later published as Dinka Christianity: The Origins and Development of Christianity among the Dinka of Sudan with Special Reference to the Songs of Dinka Christians. Faith in Sudan 11. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 2001.

Isaiah in African Church Life

Liberation theology was developed in the 1960s and 70s in the context of oppression and inequality in Latin America and amongst African Americans in North America. When liberation approaches were embraced in Africa, it could build on an existing sensitivity that Christian theology needs to address the realities of injustice, oppression and colonization. Liberation theology not only presents a proper hermeneutic in the sense that it brings to the fore other elements of the biblical message with a particular focus on liberation and on the Exodus as the foundational event in the history of Israel. It is also a new hermeneutical method. It is characterized by the sequence of see-judge-act in which the understanding of the meaning of the Scriptures begins with an understanding of the context, particularly the realities of oppression and injustice. This seeing can never be done from a distance, but must always be done while engaged in the struggle for liberation. Social analysis, often with the help of analytical tools borrowed or adapted from the Marxist tradition is then followed by the need to judge this situation with the help of the Scriptures. In this approach the social sciences take the place traditionally held by philosophy and history as the preferred academic conversation partner for theology and biblical studies. This finally leads to renewed action, for biblical interpretation should not primarily lead to new theological insights but to new liberating courses of action. A second hermeneutical principle is that God’s preferential option for the poor is not only a thesis with regard to the content of the biblical message. It is also an epistemological preference for the perspective of the poor from which one can understand both the nature of their struggles to which the Scriptures speak and to understand the revolutionary message of the Scriptures itself, which may well escape the powerful or may be suppressed by them.

Translation, Contextualization and Liturgical Use

The Book of Isaiah is sometimes referred to as “the fifth Gospel” and it plays a central role in African church life, as the following three subsections illustrate. Understanding this role is important for Old Testament scholarship on Isaiah. As part of the process of Bible translation and interpretation, the academic discipline of Old Testament studies has a responsibility for understanding the language and culture of the sender side. Nevertheless, as the African guild of Old Testament studies so clearly shows, also in its interpretation of the book of Isaiah, the discipline cannot ignore the experiences and concerns of the receiver side.

Ekem, John D. K. “Translating Asham (Isaiah 53:10) in the Context of the Abura-Mfantse Sacrificial Thought.” Trinity Journal of Church and Theology 12, no. 1 (2002): 23–29. exporter

The article argues that the Hebrew word asham in Isaiah 53:10 should be translated ahyɛnanmuadze in Abura-Mfantse: “that which is put forward as a representative offering for the community.” Also, the article calls for “the development of Study Bibles based on sound exegetical principles that will guide users to arrive at a balanced understanding against the background of their own contexts” (p. 28).

Holter, Knut. “Some Interpretative Experiences with Isaiah in Africa.” In Studies in Isaiah: History, Theology and Reception, edited by Tommy Wasserman, Greger Andersson, and David Willgren, 181–99. New York: Bloomsbury, 2017. exporter

Starting with a case from Madagascar—the echo of Isaiah 6:3 in the Eucharistic liturgy of the Malagasy Lutheran Church, where the song of the seraphim is expressed with terminology from traditional Malagasy religion—the article discusses the Book of Isaiah in relation to three African interpretive contexts: popular, church, and academic contexts. The fact that the song of the seraphim is used globally reflects what Lamin Sanneh calls the translatability of the Bible and Christianity. For an example of the Sanctus in Malagasy, see the section ‘Primary Resources Online.’

Wendland, Ernst R., and Salimo Hachibamba. “‘Do You Understand What You Are Reading (Hearing)?’ (Acts 8:30): The Translation and Contextualization of Isaiah 52:13-53:12 in Chitonga.” In The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories, and Trends, edited by Gerald O. West and Musa W. Dube, 538–56. Leiden: Brill, 2000. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Philip’s question to the Ethiopian dignitary, “Do you understand what you are reading?,” receives an immediate response: “How can I, unless someone guides me?” This response underlies the discussion of this article, which focuses on the quality of Scripture use in Africa, using the older version of the Tonga Bible (New Testament 1949, Bible 1963) as a case and ordinary Bible readers as informants.

Preaching

The relation between biblical text and sermon varies from the historical churches with their lectionaries to the African Initiated, Pentecostal and charismatic churches with their freer approach. Generally speaking, however, Old Testament texts—and not least Isaiah texts—are more visible in African churches than in their Western counterparts. For examples of sermons, see the section ‘Primary Resources Online.’

Cox, Roland P. “The Realization of Isaiah 61 in Africa: Research.” Conspectus 28, no. 1 (September 2019): 120–38. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article suggests that some aspects of Isaiah 61 have been realized in Africa: the good news has been preached and many Africans have accepted Christ and follow him. Other aspects, however, await a fuller realization, including “fighting injustice and helping the oppressed, hungry, naked and homeless” (p. 135).

Mijoga, Hilary B. P. Preaching and the Bible in African Churches. Nairobi: Acton, 2001. exporter

Analyses preaching in both mainstream churches and African Independent Churches, including several references to Isaiah. For example, in a sermon based on Isaiah 6:1–12 the preacher contextualizes the text for his own congregation and concludes: “‘Woe is for me for I am a prostitute! Woe is for me for I am a thief! Woe is for me for I am a gossip monger! Woe is for me for I am a witch!’ With such a confession, our God will summon us to go to faraway places to preach and bring back his lost souls. […] The Lord is calling you today saying, ‘Whom shall I send and who shall go for us?’ Respond to his call by repenting and confessing that Jesus Christ is Lord and Saviour. The moment you make this confession, it will not be you again, but it will be Christ in you. Amen” (p. 98–99).

Nel, Marius. “Isaiah 53 and Its Use in the New Testament and Classical Pentecostal Churches in Southern Africa.” Australasian Pentecostal Studies 21, no. 1 (December 6, 2020): 70–90. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Discusses the use of Isaiah 53 in the Apostolic Faith Mission (AFM) of South Africa based on archival and empirical research. Concludes that early AFM literature reveals a tendency to oversimplify the relation between salvation and healing, which was later partly corrected. Furthermore, contemporary AFM readers tend to straightforwardly apply the text to their personal situations without reflecting on its historical context (p. 87).

Turner, Harold W. Profile through Preaching: A Study of the Sermon Texts Used in a West African Independent Church. London: Edinburgh House Press, 1965. URL: lien web accès: exporter

A classic study of 8,000 sermons within Nigerian Aladura churches. Turner’s material shows that references to Isaiah concentrate on certain themes: the call to repent, 1:16–20; cleansing and calling, 6:1–10; the church year, 9:1–7 and 53; and fasting, 58 (pp. 65–67).

Umorem, Gerald Emem. “The Nature and Import of the Call Narrative in Isaiah 6 and Its Lessons for Ministry Today.” In The Bible on Ministries and Ministers, 1–22. Vol. 14 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2022. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article is a close reading of Isaiah 6, emphasizing that God called the prophet and arguing that this is a challenge in today’s society where many ‘prophets’ have called themselves.

Study Bibles

‘Study Bible’ is a relatively new genre, aiming to provide immediate reading assistance or interpretive aid to “lay” or “ordinary” readers who have not explicitly been exposed to the historical and critical perspectives that dominate traditional scholarship. As such, the format of the Study Bible allows its editors to give explanatory introductions and footnotes according to their denominational and theological profiles. The following three English examples make use of existing (Western) Bible versions but then add introductions and footnotes aimed at the African readership.

Holter, Knut. “Interpretive Context Matters: Isaiah and the African Context in African Study Bibles.” In The Oxford Handbook of Isaiah, edited by Lena-Sofia Tiemeyer, 655–69. Oxford University Press, 2020. URL: lien web accès: exporter

A critical study of the presentation of Isaiah in three African Study Bibles: The African Bible (1999, Roman Catholic), Prayer and Deliverance Bible (2007, Pentecostal), and Africa Study Bible (2016, mainstream Protestant).

Jusu, John, ed. Africa Study Bible. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2016. exporter

A mainstream Protestant example with a typically Evangelical profile. The Isaiah section is characterized by conservative claims regarding questions of authorship, but also an emphasis on socio–critical concerns and possibilities for inculturation. Furthermore, it includes warnings against syncretism, such as the following comment on the passage about idol fabrication in Isaiah 44:9–20: “Why does a pregnant woman put a Bible under her pillow? She feels confident that God will never allow anything bad to happen to her or her baby during the vulnerable night. When the Bible is used in this way, it has become a fetish” (p. 1036).

Olukoya, Daniel K., ed. The Prayer and Deliverance Bible. Lagos: Mountain of Fire and Miracles Ministries, 2007. exporter

This example is not a typical Study Bible but is included here due to its influence in parts of the Pentecostal movement. It focuses on spiritual warfare, sometimes at the cost of the historical interpretation of the text. An illustrative example is a note about Isaiah 15:1, which describes how cities in Moab are destroyed during the night. The note connects this with the nocturnal activities of spiritual powers, such as water spirits that are said to take the form of prostitutes: “They carry out their activities in the night. Many of them are found in the streets at night. They roam the streets as ladies looking for men who will give them a lift. ” (p. 136).

Zinkuratire, Victor, and Angelo Colacrai, eds. The African Bible. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 1999. exporter

The Isaiah section is characterized by typical Catholic inculturation hermeneutics as well as an openness to the concerns of critical biblical studies. An illustrative example is the comment about Cyrus, king of Persia, in 41:2: “People outside the Christian churches practice virtue and goodness. This needs to be emphasised especially in the context of inculturation. Africa can receive the message of Christ and transform it in an African way. The message of Christ has to be incarnated in the customs, mentality and culture of the African, because the customs, mentality and culture of Africa are already a natural proclamation of the Gospel” (p. 1257).

Isaiah in African Academia

The following presentation of ‘Isaiah in African Academia’ focuses on works with a conscious contextual concern, which explicitly refer to African interpretive contexts and experiences, and highlights several key themes. For a comprehensive list of works on Isaiah in African Academia, see Holter et al. 2024 in the section ‘Bibliographies’.

The Prince of Peace and Peace–making in Africa

The Immanuel texts in Isaiah 7–11 depict a ruler who establishes peace and justice. These texts, in particular 9:1–6, attract comparative African perspectives, often reading the texts in light of their New Testament and Christological reception.

Kahindo, Veronique. “Prince of Peace for the Kingdom of Judah in Crisis: A Contextual Reading of Isaiah 9:1-6 from the Perspective of Peace-Building Efforts in the Eastern Provinces of the DRC.” PhD diss., University of South Africa, 2016. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The dissertation analyses Isaiah 9:1–6, using a tri-polar exegetical model developed by Justin Ukpong. The text is read in dialogue with people in the eastern part of the DRC, who—like the Judean first readers of the text—yearn for a righteous, faithful, and legitimate Prince of Peace who is willing to put an end to the interminable violence they experience.

Kruger, H. A. J. “Infant Negotiator?: God’s Ironical Strategy for Peace: A Perspective on Child-Figures in Isaiah 7-11, with Special Reference to the Royal Figure in Isaiah 9:5-6.” Scriptura 44 (1993): 66–88. DOI: 10.7833/44-0-1655 accès: exporter

Kruger suggests a way of appropriating the texts to address the violent situation in South Africa during the final years of apartheid. He proposes a messianic model that connects the peace-making of the messianic child with the work of Jesus in the New Testament and proclaims him as the ultimate source of peace for South Africa. Furthermore, he suggests that “by being properly instructed in schools, children can be bearers of the reality of peace” (p. 84).

Kruger, H. A. J. “Isaiah 9:5-6 and Peace in South Africa: An Exercise in Inner-Biblical Exegesis.” Nederduits Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 34 (1993): 3–14. exporter

The article presents various summary exegetical comments on Isa 9:5–6 in the context of 8:23b–9:6. Thereafter, Kruger proceeds to an intra–textual study concerning the figure of the ‘marshal of peace’ cited in 9:5, comparing that figure with Deutero–Isaiah’s portrayals of Cyrus and the Servant and the New Testament depiction of Jesus. The article closes with reflections on preaching the Isaianic text in the South African situation.

Nwaoru, Emmanuel O. “Prince of Peace (Is. 9:5-6): A Messianic Title for African Christology.” In Christology in African Context, edited by Samuel O. Abogunrin, John O. Akao, Dorcas O. Akintunde, and Godwin N. Toryough, 54–76. Lagos: Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, 2003. exporter

In dialogue with some exegetical perspectives on Isaiah 9:5 and current Christological reflection, Nwaoru argues that the title ‘Prince of Peace’ in Isaiah 9:5 (v. 6 in English translations) fits African concepts and can be used vis–à–vis challenges such as “endless guerrilla warfare destabilizing the civil order, frequent coup d’etat reversing political and social reforms, abject poverty, hunger and disease staring the citizenry, especially women and children in the numerous refugee camps in the face” (p. 67).

Onwukeme, Victor. “War and Peace in Isaiah 11:1–10: An Evaluation of the Nigerian Context.” In War and Peace in the Bible, edited by Anthony Odafe, Gerald Emem Umorem, Cosmas Uzowulu, and John Jimoh, 265–79. Vol. 16 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2024. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article discusses the peace vision in Isaiah 11:1–10 from exegetical (Old Testament and Ancient Near East) and reception-historical (New Testament and church history) perspectives. This is followed by a contextual reflection, seeing conversion to Christ as the only solution to the problems caused by tribalism and corruption in contemporary Nigeria.

Ramantswana, Hulisani. “Not Free While Nature Remains Colonised: A Decolonial Reading of Isaiah 11:6-9.” Old Testament Essays 28, no. 3 (2015): 808–32. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article analyses Isaiah 11:6–9 and relates it to the contemporary South African context, in which the relation between humans and nature continues to be shaped by colonial patterns. The article argues that “human freedom is intertwined with the freedom of nature and therefore the two should not be separated. Decolonisation remains incomplete as long the colonial matrix of power that divides African humans from nature persists” (p. 808).

Ritchie, Ian D. “The Nose Knows: Bodily Knowing in Isaiah 11.3.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 25, no. 87 (March 2000): 59–73. DOI: 10.1177/030908920002508704 accès: exporter

The Hebrew text of Isaiah 11:3 uses the idea of “smelling” to describe the Messiah figure’s ability to discern good from evil. Bible interpreters have traditionally seen the text as corrupt and suggested textual reconstructions. However, with African anthropological (and traditional rabbinical) material, the article advocates a reading that acknowledges the “smelling” sense of the Hebrew text.

Unigwe, Rosemary Ifeyina. “Inter-Personal Relationship in Isaiah 11:6-9 and Its Implication in Nigeria.” In The Bible on Human Beings, Race and the Land, edited by s.n., 109–21. Vol. 13 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2021. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Unigwe argues that the description made by Isaiah in 11:6-9 may seem far-fetched in the Nigerian context of today, a utopian fantasy that could never be reality. Yet it accurately describes conditions during the future earthly kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Unigwe, Rosemary Ifeyina. “Isaiah 32:15–18: Establishing Justice as the Bedrock for Peace and Its Implications in Addressing Insecurity, Religious Crisis and Tribal Conflict in Nigeria.” In War and Peace in the Bible, edited by Anthony Odafe, Gerald Emem Umorem, Cosmas Uzowulu, and John Jimoh, 224–47. Vol. 16 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2024. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article reads Isaiah 32:15–18 in the context of contemporary Nigeria, with a focus on the profound connection between justice and peace. It is argued that this connection could serve as a cornerstone for addressing the complex issues of insecurity, religious disputes, and tribalism in Nigeria.

Yilpet, Yoiliah K. “The Anointing Work of the Holy Spirit in Isaiah 11:1–5, 42:1–7, 61:1–3.” African Journal of Biblical Studies 26, no. 1 (2008): 112–33. exporter

The article discusses three Isaianic texts as background for the Christian concept of the Holy Spirit, arguing that the anointing of the Holy Spirit relates to someone who is filled with the Spirit’s power for service and witness for God’s glory, and who is controlled and guided to do God’s will.

The Suffering Servant and Salvation in Africa

The so–called Servant Songs in Isaiah 42–53 depict a person (or collective) who embodies key theological perspectives such as universalism/particularism and vicarious suffering. These perspectives have been crucial throughout the history of biblical interpretation and African biblical interpretation continues this line of interpretation, reading the texts together with African experiences and concerns, not least questions of suffering.

Ejeh, Theophilus U. The Servant of Yahweh in Isaiah 52:13-53:12: A Historical Critical and Afro-Cultural Hermeneutical Analysis with the Igalas of Nigeria in View. Zurich: LIT Verlag, 2012. exporter

The book attempts to build a bridge between Isaiah 52:13–53:12 and the life and culture of the Igala of Nigeria. After a historical-critical interpretation and a reading of the text in light of its New Testament reception, it is related to the language and worldview of the Igala.

Kabasele Lumbala, François. “Isaiah 52:13-53:12: An African Perspective.” In Return to Babel: Global Perspectives on the Bible, edited by John R. Levison and Priscilla Pope-Levison, 101–6. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999. exporter

Kabasele Lumbala starts with a narrative about a fifty-year-old widow and mother of eight children from the DRC and some of the sufferings she has gone through. He relates her experiences to those of the ‘suffering servant’ in Isaiah 52:13–53:12, reflecting on how the text resonates with daily experiences.

Okambawa, Wilfrid. “The Healing of Patient: African HIV and AIDS Hermeneutics of Isaiah 52:13-53:12 (with Special Focus on Isaiah 53:5).” In HIV & AIDS in Africa: Christian Reflection, Public Health, Social Transformation, edited by Jacquineau Azétsop, 117–30. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2016. exporter

The article discusses how the ‘suffering servant’ of Yahweh in Isaiah 52:13–53:12, the most influential Isaiah text in the shaping of New Testament Christology, can be understood as a ‘healing patient’ when the expression “and by his wounds we are healed” in 53:5 is read in light of therapeutic stories in African Traditional Religion. Here, the patient is the best one to heal other people. The article relates this to experiences with HIV and AIDS, arguing that the victims can become healers and salvific agents for others.

Rugwiji, Temba. “The Salvific Task of the Suffering Servant in Isaiah 42:1-7: A Contemporary Perspective.” Journal for Semitics 23, no. 2 (January 2014): 289–314. DOI: 10.25159/1013-8471/3492 accès: exporter

Rugwiji examines salvific themes in Isaiah 42:1–7, including the scope and nature of salvation and the identity of the ‘suffering servant’. He suggests that “the suffering servant in the servant songs can be anybody whose contribution to the liberation and emancipation of society has been a grand achievement in the history of humanity” (p. 311). Furthermore, he highlights Nelson Mandela as a contemporary example.

Wendland, Ernst R., and Salimo Hachibamba. “‘Do You Understand What You Are Reading (Hearing)?’ (Acts 8:30): The Translation and Contextualization of Isaiah 52:13-53:12 in Chitonga.” In The Bible in Africa: Transactions, Trajectories, and Trends, edited by Gerald O. West and Musa W. Dube, 538–56. Leiden: Brill, 2000. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Philip’s question to the Ethiopian dignitary, “Do you understand what you are reading?,” receives an immediate response: “How can I, unless someone guides me?” This response underlies the discussion of this article, which focuses on the quality of Scripture use in Africa, using the older version of the Tonga Bible (New Testament 1949, Bible 1963) as a case and ordinary Bible readers as informants.

Visions of Hope and Socio–Economic Liberation in Africa

A number of Isaianic texts offer visions of hope describing the salvation that God will accomplish for his people. These texts are popular in African political discourse, in which they are often used for rhetorical effect. They are also prevalent in African biblical interpretation, in which they are read in relation to African longings for socio-economic liberation, justice and transformation.

Cezula, Ntozakhe S. “Waiting for the Lord: The Fulfilment of the Promise of Land in the Old Testament as a Source of Hope.” Scriptura 116, no. 1 (2017): 1–15. DOI: 10.7833/116-1-1304 accès: exporter

Cezula compares how the books of Ezra-Nehemiah and Isaiah present the fulfilment of God’s promise of land to Abraham. He concludes that “Isaiah 19:16-25 exhibits a universalistic and inclusive nuance that presents God’s redemptive blessings as available for all peoples, regardless of ethnicity,” and suggests that this theological strategy “can render the promise a source of hope for all Christian communities in (South) Africa” (p.12).

Cox, Roland P. “The Realization of Isaiah 61 in Africa: Research.” Conspectus 28, no. 1 (September 2019): 120–38. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article suggests that some aspects of Isaiah 61 have been realized in Africa: the good news has been preached and many Africans have accepted Christ and follow him. Other aspects, however, await a fuller realization, including “fighting injustice and helping the oppressed, hungry, naked and homeless” (p. 135).

James, Genevieve L. “Urban Theology Endeavours and a Theological Vision of Hope and Justice for Post-Apartheid South African Cities.” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1, no. 2 (2015): 43–68. DOI: 10.17570/stj.2015.v1n2.a02 accès: exporter

James draws on Isaiah 65:17–24 to offer a theological vision for urban renewal in South Africa. He argues that “the task of the church is to permeate the urban environment with the Christian joyfulness and hope” (p. 58). Furthermore, the church should work towards the provision of healthcare, shelter and a just economy (pp. 59-63).

Le Roux, Jurie H. “Two Possible Readings of Isaiah 61.” In Liberation Theology and the Bible, edited by P. G. R. De Villiers, 31–44. Pretoria: University of South Africa, 1987. exporter

The article discusses Isaiah 61 – the text about freedom for captives and release from darkness for prisoners – which is used by Luke 4 to portray the ministry of Jesus and is frequently referenced in liberation theology. One perspective interprets freedom as present reality (materialist exegesis), attending to the poor (in a literal sense) and oppressed in society and their ‘liberation’ here and now. The other interprets it as a future reality. The article argues in favour the former.

Mangayi, Lukwikilu C., and Themba E. Ngcobo. “A Vision for Peace in the City of Tshwane: Insights from the Homeless Community.” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 71, no. 3 (2015): 1–9. DOI: 10.4102/hts.v71i3.3097 accès: exporter

Mangayi and Ngcobo explore the perspectives of homeless people on peace in Tshwane. They engage in theological and ‘encounterological’ reflection on Isaiah 65:17–25, drawing on empirical research involving ‘Contextual Bible Study’ with twelve participants. The latter read the text as a holistic vision of peace promised by God, not only for Israel or Christians, but for all residents of Tshwane, who need to consciously work together towards its realisation.

Mtshiselwa, Ndikho. “Reading Isaiah 58 in Conversation with I. J. Mosala: An African Liberationist Approach.” Acta Theologica 36 (2016): 131–56. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Mtshiselwa uses an African liberationist approach that draws on the work of Itumeleng J. Mosala and the notion of Ubuntu to read Isaiah 58 in the context of oppression and poverty in Southern Africa. He argues that “Isaiah 58 could contribute positively to socio-economic redress in terms of poverty alleviation and, subsequently, to building relationships in Southern Africa when read from an African liberationist perspective” (p. 149).

Punt, Jeremy. “Popularising the Prophet Isaiah in Parliament: The Bible in Post-Apartheid, South African Public Discourse.” Religion & Theology 14, no. 3–4 (2007): 206–23. DOI: 10.1163/157430107X241285 accès: exporter

At the opening of the South African parliament in 2006, President Thabo Mbeki made several references to Isaiah 55:12–13a in his State of the Nation address. The article analyses the use of Isaiah in Mbeki’s speech and in the responses of the opposition parties. Punt argues that the politicians take a similar hermeneutical approach, selectively applying fragmented texts directly to the South African context.

Other Studies on Isaiah and Africa

In addition to the studies listed in the thematic sections above, there are a number of other works with a conscious contextual concern that are worth mentioning.

Acha, Agnes. “The Motif of the Word of God in the Prologue (Isa 40:1-11) and Epilogue (Isa 55:6-11) of Deutero-Isaiah.” In Alive and Active: Images of the Word of God in the Bible., edited by Teresa Okure, Luke E. Ijezie, and Camillus Umoh, 85–102. Vol. 1 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2012. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Acha provides a close reading of Isaiah 40:1–11 and 55:6–11, pointing out the focus on the Word of God in a situation of despair and hopelessness, and relates this briefly to the Nigerian context.

Acha, Agnes. “‘These People Honour Me with Their Lips’: A Study of Isa 29:13 and Its Implications for Faith and Evangelisation in Nigeria.” In The Bible On Faith and Evangelization, edited by Anthony Ewherido, Bernard Ukwuegbu, Mary Jerome Obiorah, and Joseph Haruna Mamman, 27–36. Vol. 6 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2015. URL: lien web accès: exporter

The article discusses Isaiah 29:13—a text on hypocrisy— in dialogue with some other Old Testament texts with a similar motif and relates it to questions about faith and evangelization in Nigeria.

Igbo, Peter. “Isaiah’s Message of Nonviolence in Isaiah 2:1-4: Implications to the Societal Wellbeing.” In The Bible on Human Beings, Race and the Land, edited by s.n., 95–109. Vol. 13 of Acts of the Catholic Biblical Association of Nigeria. Port Harcourt: CABAN, 2021. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Igbo analyses Isaiah 2:1–4 and relates it to the Nigerian context, where violence and armed conflict have contributed to poverty and underdevelopment. He argues that peace education is key to establishing a peaceful society where all can flourish (p. 107).

Ogunkunle, Caleb O. “Prophet Isaiah and the Healing of King Hezekiah in the African Context.” In Biblical Healing in African Context, edited by Samuel O. Abogunrin, John O. Akao, Dorcas O. Akintunde, Godwin N. Toryough, and Paul A. Oguntoye, 51–63. Lagos: Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, 2004. exporter

The narrative about King Hezekiah in Isaiah 36–39 (see also 2 Kings 18–20 and 2 Chronicles 29–32) includes a section on the king’s sickness and healing (Isaiah 38). Ogunkunle reads this from the perspective of healing practices in traditional Yoruba contexts and in Aladura churches.

Olanisebe, Samson O. “The Justice of God in His Anger: A Narrative Analysis of Isaiah 5:1-7 and Its Implications for Socio-Economic and Security Challenges in Nigeria.” Old Testament Essays 28, no. 2 (January 2015): 481–96. URL: lien web accès: exporter

Olanisebe examines Isaiah 5:1–7 and explores its implications for the Nigerian situation, in which economic and political problems persist despite an abundance of human and natural resources. He particularly emphasises “the lasting relevance of the messages of Israel’s prophets without recourse to differing cultural contexts and distance in time and space” (p. 494).

How to Cite This Resource

Holter, Knut. “Isaiah.” Bibliographical Encyclopaedia of African Theology. 31 December 2024. Accessed [enter date]. https://african.theologyworldwide.com/encyclopaedia/404-isaiah.

Photo: Detail of a parchment folio from the book of Isaiah in Geʽez. Endangered Archives Programme. “Excerpt from Isaiah, Book of Ezekiel, Life of Ezekiel, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees [Late 15th Century–Early 16th Century].” British Library. Accessed 31 December, 2024. https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-426.