ATW Blog

Over the past fifty years, African women have made remarkable headway in the area of theological education. In this blog I present a variety of resources – most of which are freely accessible – including books, chapters, articles, videos and websites, that together provide a helpful overview of this important topic.

Du 15 au 19 décembre 2025, l’équipe d’African Theology Worldwide (ATW) ou la « Théologie africaine à travers le monde » (TAM) s’est réunie au centre de conférences de Brackenhurst à Limuru, au Kenya, pour une consultation et une rencontre avec des éducateurs théologiques et chercheurs africains. Cette rencontre s’inscrit dans la dynamique globale d’ATW visant à rendre la théologie africaine plus visible, plus accessible et plus collaborative au service de l’Église et du monde académique. Elle vise à renforcer la visibilité, la collaboration et la qualité de la théologie africaine.

Five years ago, I wrote a blog post titled Recommended books for Apologetics in Africa. I limited the discussion to key resources that are written for the African context. Since then, I have edited a book titled Apologetics in Africa: An Introduction to help capture biblical, philosophical, cultural and practical ministry perspectives from top African theologians and scholars. However, in this post I am imagining someone totally new to the discussion on African Apologetics and asking “where can I start?”

Du 21 au 28 Septembre 2024, j’ai eu le privilège de prendre part pour la première fois au Congrès du Mouvement de Lausanne, dénommé Lausanne 4, qui s’était déroulé à Séoul en Corée du Sud. Cette édition était organisée par le Comité Exécutif Global et son thème était “Qu’ensemble l’Église proclame et mette en évidence le Christ”.

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to participate in the 6th Pan-African Conference of the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians. The conference was hosted by Trinity Theological Seminary in Accra, Ghana, from 1 to 5 July and its theme was Sankofa 2024: Earth, Pandemics, Gender and Religion. I had expected the conference to be a multicultural event, but the reality was even more diverse than I had imagined. This diversity was enriching, but also challenging at times.

Why study Christian history? Knowledge (or ignorance) of history impacts identity: “a past is vital for all of us—without it, like the amnesiac man, we cannot know who we are” and thus “what is the past of the African Christian” will remain a prime question for African theology (Walls 1978, 13).

On 15 June 2023, Shri Piyush Goyal, India’s minister of Union Commerce and Industry, claimed that India and Africa are “natural partners with historical and cultural ties” (Government of India 2023). It is hard to imagine that these ties do not include theological exchange, considering that there is a history of intercultural exchange between the two (Shankar 2021).

Recent Christian ecotheology has emerged in the wake of Lynn White Jr.’s assertion that Christian theology promotes environmental destruction and is the cause of the modern ecological crisis (Gottlieb 2004, 201). Conversations in this field have paved the way for African ecotheology, which aims to contribute to local and international ecological discourses by reflecting on the underlying causes of and solutions to environmental degradation in African contexts and around the world.

Ever since the South and West came into contact, there have been various interactions and relations which have had both positive and negative consequences. These interactions continue today in various forms. Two spheres of this South-West interaction dating back to the first contact are Christianity and commerce. While both parties have developed significantly in both areas, independently and cooperatively, there is still room for improvement, especially when Christianity and finance merge in Christian missions.

The blood of Jesus is a popular theme in African Christianity with deep roots in the Bible and African traditions (see Machingura and Museka 2016). Before the arrival of European and African missionaries, blood was an important symbol in many African religions and was used for a variety of ritual purposes. The missionaries realised this and emphasised the power of the blood of Jesus in their sermons and hymns. Soon African Christians took up the theme, developing it in new ways.

The spread of African Christianity from Africa to the entire world is one of the most fascinating things about the religious landscape of the twenty-first century. African Christians have been migrating to other continents in large numbers over the past five decades. The Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), for example, states that it is present in 197 countries around the world — most of their members are Nigerians who have migrated from their homeland to these countries.

Philip Jenkins has highlighted the demographic shift of Christianity from the North to the Global South which includes Christians on three continents: Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Despite this development, the churches in Asia and Africa continue to focus their attention primarily on Christians in the West. Nevertheless, in the past two decades African Christians have begun to make contributions to theological thinking in South Asia.

Za mtu ni mbili–akili na haya.

The [best qualities] of a person are two—intelligence and modesty.

A Swahili proverb is apt in honouring our deeply cherished brother, Fr. Prof. Laurenti Magesa (1946-2022). News of his passing on August 11, 2022, in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, prompted outpourings of grief and respect from across Africa and beyond.

From 31 August to 8 September, I had the privilege of participating in the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, held in Karlsruhe, Germany, as delegate for the Protestant Church in the Netherlands. It was great to see the important role of Sub-Saharan Christianity acknowledged in the assembly, not only in the significant number of African delegates, but also in the role of Dr Agnes Aboum from Kenya as the principal moderator and the presentation of Dr Jerry Pillay from South Africa as the new General Secretary.

Earlier this year, I had the privilege of attending a service held by the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Wezep. The church mainly consists of Eritrean migrants who have recently arrived in the Netherlands as refugees and has been meeting regularly since December 2017. I was invited by a family who were having their fourth child baptized.

One of the goals of the BEAT is to point readers to relevant primary resources on the internet that will help bring the subject to life. The aim is to show the connection between African theological discourse and the grassroots theologies of African Christian communities. In this post I introduce the primary resources section from a recent article on sacrifice and explain the rationale for the selection.

Some months ago, I was teaching a class on the contribution of lived theologies from different cultural contexts to intercultural theological conversations. We focussed on experiences of the Holy Spirit in Pentecostalisms worldwide. Three of the students gave presentations on this theme, drawing on examples from their own cultural contexts.

On Christmas Day 2021, South Africans woke with the news that our bishop has passed on. In no time, typical of the African storytelling tradition, stories about Bishop Tutu were all over the media. People from all walks of life shared their stories of how they met this loving, remarkable man. I will join this avalanche of endearing stories by sharing two, one before 1994 and one after 1994.

The death of the Ecuadorian theologian René Padilla on the 27th of April 2021 calls for reflection on the continuing relevance of his missiology today. Though the specific context of Padilla's missiological reflection is Latin America, his contribution to the birth of ‘integral mission’, or ‘misión integral’ in Spanish, has profoundly impacted evangelical theological discourse around the world.

The term ‘intercultural theology’ was first used to refer to a particular field of study in 1975 when Hans Jochen Margull, Walter Hollenweger and Richard Friedli started publishing a book series called Studies in the Intercultural History of Christianity. Hollenweger also used it to indicate a theological approach in a three-volume collection of shorter pieces. Intercultural theology only became the name for a specific discipline when a number of professorial chairs in missiology were renamed ‘intercultural theology’.

There was once a final-year student at a theological college in the West African sub-region. The student needed to take and pass one last course in the Spiritual Formation disciplines at the college’s undergraduate program. The task specified in the course description required the student to write a personal reflection paper that accounted for the life and ministry of “Holy” James Johnson’ (c. 1836–1917).

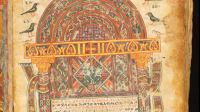

While doing research on Ethiopian Hermeneutics for the Biblical Hermeneutics encyclopaedia article, I came across a number of websites with valuable primary and secondary resources. Recent interest in the digital preservation of Ethiopian manuscripts has led to copies of paintings that were previously inaccessible being made publicly available for the first time.

Gerald West's account of African biblical interpretation suggests that how one reads the Bible is ultimately the result of one's 'ideo-theological orientation'. Does this mean that one's hermeneutical approach is merely a matter of personal choice? In this reflection I introduce two principles that are helpful when considering this question.

Help us improve the website!

- Submit Bibliography Items

- Submit Portal Items

- Submit News Items

- Submit Feedback

Featured encyclopaedia articles

Featured bibliographies

Recent blog posts

News

Newsletter

Sign up here to receive the ATW Newsletter, which provides updates about the platform and showcases valuable resources, as well as special announcements related to the field of African Christian Theology.