Introduction

Jesus’ question to his disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” (Mark 8:29), is understood to apply to believers of every generation and every place. In its singular form, ‘Christology’ is essentially the study of how Christians have responded to this question, or how they have understood and experienced Jesus Christ, who stands at the heart of our common faith. The plural form, ‘Christologies’, conveys the multiple expressions of Jesus’ identity and significance within the New Testament itself and throughout history, as believers reflect on Christ in the light of biblical revelation and their own particular situation, including culture, worldview, and experience.

African Christologies offer reflections on Jesus Christ that are interrelated with Christologies elsewhere, yet are shaped by the historical, religious, cultural, and social realities of Africans. While African Christians have naturally expressed their own perceptions and experiences of Christ ever since the gospel reached the continent, this article focuses on the proliferation of christological reflections since approximately the mid-twentieth century. Given the remarkable rise of African Christianity and the critique of certain aspects of the Western missionary movement, African believers have sought to proclaim and live out their faith in Christ in ways that are meaningful and relevant within local contexts. Significantly, these Christologies include both formal articulations in the writings of theologians and informal expressions in the ‘oral’ or ‘lived’ Christologies of Africans in their everyday lives. Furthermore, the article includes a broad range of christological reflections formed by various streams of Christian tradition, from historic mainline churches through charismatic/Pentecostal and African Independent Churches (AICs). Finally, a defining characteristic of the African Christologies presented here is that they are contextual in nature; that is, they are informed not only by biblical revelation and Christian tradition, but also by the contextual realities in which they arise.

The article is divided into various sections, beginning with a range of introductory resources: overview articles, chapters within global surveys, anthologies, bibliographies, textbooks and selected primary resources available online for free. The next two sections focus on African Christologies that are primarily biblical and doctrinal in nature. The field of African Christology is then delineated in terms of key thematic and methodological trends: inculturation and intercultural Christologies, liberation and black Christologies, and reconstruction Christologies. Following the description of this typology, certain expressions of Christology that arise from particular sources warrant consideration, including grassroots Christologies, AIC and Pentecostal Christologies, African women’s Christologies, and case studies of indigenous Christologies. The next section outlines major images of Jesus in Africa, including ancestor, healer, liberator, king, and other depictions. Finally, two broad aspects of relevance are highlighted in the sections on Christology in relation to social transformation and religious pluralism.

While the article and bibliography are not exhaustive, they aim to provide a comprehensive account of developments in contextual Christology in Africa over the past century. The proliferation of christological expression reveals the singular vitality of the Christian faith in Africa as well as the significance of African contributions to the ongoing development of Christian tradition worldwide.

Overview Articles and Chapters

This section offers a selection of introductory articles and chapters in the field of African Christology, including some of the earliest contributions as well as contemporary reflection on the subject. Together, they offer an overview of the field with the following points of note. First, the account of the experience and expressions of Jesus’ life and work in Africa is provided not simply from the privileged position of scholars, but very importantly, in light of the faith and experience of ordinary believers. Second, the understanding and interpretation of the truth about Jesus’ being and doing are done from the sources of Christian revelation and tradition, on the one hand, and from within the historical, religious, cultural and social contexts of Africans, on the other. This offers a valuable development of, and contribution to, Christology worldwide (e.g., Hinga 1994; Orobator 1994; Akper 2007. Third, the purpose of many African scholars is not only to interpret the theological content of Jesus’ identity and ministry, but also to discern and commend the enduring fruits of Jesus’ life and work in Africa for the faith and life of Africans today (e.g., Stinton 2007 – see ‘Grassroots Christologies’ – and Stinton 2015).

Akper, Godwin I. “The Person of Jesus Christ in Contemporary African Christological Discourse.” Religion & Theology 14, no. 3/4 (September 2007): 224–43. DOI: 10.1163/157430107X241294 URL: Link Access: Export Item

Akper explores how contemporary African theologians have interpreted and appropriated the person and work of Jesus Christ. He introduces three main perspectives: African Christology, black Christology, and African women’s Christology. Akper’s exposition and critical evaluation of representative thinkers in each domain leads him to propose some methodological, contextual, and theological building blocks for doing Christology in Africa.

Cook, Michael. “The African Experience of Jesus.” Theological Studies 70, no. 3 (2009): 668–92. DOI: 10.1177/004056390907000307 Access: Export Item

Under three rubrics – missionary, biblical, and independent – Cook explores how Africans experience Jesus and how Jesus himself experiences Africans. There is an inseparable connection between the two experiences. The former, objective sense, accounts for Africans’ expression of faith in Christ, known through ‘primal imagination’. The latter, subjective sense, speaks of Jesus’ own faith in or fidelity to the experience of African people, known by means of the ‘paschal imagination’.

Hinga, Teresia M. “Christology and Various African Contexts.” Quarterly Review: Journal of Theological Resources for Ministry 14, no. 4 (1994): 345–57. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Kenyan theologian Hinga discusses the importance of contexts, contextuality or contextualisation. In light of this, Hinga upholds the view that christologising entails a dialogue between the eternal, transcendent Word of God and the particular, ever-changing world of human beings. This ‘Word-world encounter’ is at the heart of, and is the basic theme of, Christology in Africa.

Manus, Ukachukwu Chris. “African Christologies: The Centre-Piece of African Christian Theology.” Zeitschrift Für Missionswissenschaft Und Religionswissenschaft 82, no. 1 (1998): 3–23. Export Item

Manus argues that Christian theology, the study of God’s self-revelation and its implication for the life of the world, is founded upon and sustained by reflections about Jesus Christ. In other words, Christology forms the centre of gravity of Christian theological reflections, especially in the contemporary African theological landscape where the person and work of Christ are at the heart of the (re)imagination of God and human existence.

Mbiti, John S. “Some African Concepts of Christology.” In Christ and the Younger Churches: Theological Contributions from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, edited by Georg F. Vicedom, 51–62. Theological Collections 15. London: SPCK, 1972. Export Item

In one of the earliest essays on African Christology, Mbiti, a well-known Kenyan Anglican theologian, makes the provocative statement that “African christological concepts do not exist” (p.51). His intent was not to criticise but rather to challenge African theologians to produce a distinct Christology deriving from the life, faith, and experiences of Africans. The remainder of the essay offers an example and some pointers for fulfilling this christological task.

Mbiti, John S. “For Now We See in a Mirror Dimly: The Emerging Faces of Jesus Christ in Africa.” In Cristologia e Missione Oggi, edited by G. Colanzi, P. Giglioni, and S. Karotemprel, 143–64. Vatican: Urbaniana University Press, 2001. Export Item

In a later christological reflection, Mbiti situates the discourse within the African religious-cultural context, arguing that Christ was already present in indigenous religions and practices. This Christic presence grounds and enables the growth and flourishing of faith in Christ in Africa. It also allows for the dynamic ways in which Africans experience and appropriate Jesus in images, like master of initiation, ancestor, healer, liberator, and some feminine images.

Moloney, Raymond. “African Christology.” Theological Studies 48, no. 3 (1987): 505–15. DOI: 10.1177/004056398704800305 URL: Link Access: Export Item

Moloney provides an account of the earliest development of Christology in Africa in terms of its dual tasks: inculturation and liberation. Inculturation Christologies seek to understand and communicate faith in Jesus Christ from indigenous perspectives and experience. Christologies of liberation reflect on Jesus Christ in the light of the social, political, and economic realities of people in Africa.

Nyamiti, Charles. “African Christologies Today.” In Faces of Jesus in Africa, edited by Robert J. Schreiter, 3–23. Faith and Culture Series. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Nyamiti, an early proponent of African Christology, introduces its line of development and progress to date in Africa. He underlines the diversity and multiplicity of christological expressions in African Christianity. Discussing various images of Jesus like ancestor, healer, and liberator, Nyamiti shows how the diverse Christologies converge on the one Christ who is truly and fully both God and human. Originally published in Mugambi and Magesa 1989 (see ‘Anthologies’).

Orobator, Agbonkhianmeghe. “The Quest for an African Christ: An Essay on Contemporary African Christology.” Hekima Review 11 (September 1994): 75–99. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Orobator analyses three christological models: Christ-as-Ancestor, Christ-as-Chief, and Christ-as-Guest. He outlines the ancestor model, focusing on Nyamiti’s ‘brother-ancestorship’ and Bujo’s ‘proto-ancestorship’; the chief model; and Udoh’s guest model. In his evaluation, the ancestor and chief models fail to sufficiently recognise Christ’s newness in Africa. He favours the guest model because it presupposes Christ’s initiation into African culture, thereby validating Jesus’ lordship in Africa.

Stinton, Diane. “Jesus Christ, Living Water in Africa Today.” In The Oxford Handbook of Christology, edited by Francesca Murphy, 426–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. www.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641901.013.25. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Stinton offers a seminal reflection on the person and significance of Jesus Christ in Africa as ‘life-giver’, ‘mediator’, ‘loved one’, and ‘leader’. She frames her insights in relation to three African proverbs, thereby demonstrating that African Christologies, while reflecting constructive, contextual engagement with the identity and significance of Jesus Christ, “stand squarely in the river of biblical, historical, and systematic Christian tradition” (p. 427).

African Christology within Global Surveys

With the rise of contextual theologies in the latter half of the twentieth century, global surveys of Christology naturally emerged. Each of the following surveys acknowledges the significance of African contributions to Christology and, accordingly, allocates considerable attention to this topic within the wider context of the volume. Wessels 1990 is an early survey by a Dutch theologian that examines wide-ranging depictions of Jesus in art, liturgy, and theology, questioning in what ways Jesus has been portrayed and betrayed in the various cultural representations. Küster 2001, by a German theologian, takes an intercultural perspective in analysing global Christologies, seeking to establish models of Christology based on commonalities and divergences, and to suggest opportunities for ecumenical learning. Kärkkäinen 2003, by a Finnish theologian, examines four first-generation African theologians for their contributions to leading christological images in relation to power. Brinkman 2009, another survey by a Dutch theologian, examines African Christology and delves further into the two particular images of Ancestor and Healer within African contexts, drawing upon the work of a variety of African theologians. While these single-authored works offer valuable introductions and individual interpretations, Green, Pardue, and Yeo advance the discussion by compiling an anthology of christological reflections by indigenous theologians around the world, with Ezigbo offering an African perspective (Ezigbo 2014).

Brinkman, Martien E. “African Images of Jesus.” In The Non-Western Jesus: Jesus as Bodhisattva, Avatara, Guru, Prophet, Ancestor or Healer?, translated by Henry Jansen and Lucy Jansen, 224–40. London: Routledge, 2009. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Brinkman focuses on two images of Jesus in this chapter: ancestor and healer. He argues that Jesus as ancestor is a key image that merits continued reflection given its contextual significance in African cultures. Brinkman then presents Jesus as healer relating healing to the centrality of ‘life’ for Africans as a concept. He concludes that these images reflect Christ’s connections to life as both the giver and saver of life.

Ezigbo, Victor I. “Jesus as God’s Communicative and Hermeneutical Act: African Christians on the Person and Significance of Jesus Christ.” In Jesus without Borders: Christology in the Majority World, edited by Gene L. Green, Stephen T. Pardue, and K. K. Yeo, 37–58. Majority World Theology Series. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2014. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Ezigbo avers that African Christology must align with scripture’s revelation of Jesus Christ, demonstrate faithfulness to the early ecumenical councils and creeds, and be relevant to the questions and experiences of African Christians. Tracing its recent development, he outlines three christological models: neo-missionary, ancestor, and his own proposal of revealer Christology. Jesus reveals both divinity and humanity so that through him, African Christians can redirect their prior knowledge of God. Republished in Majority World Theology: Christian Doctrine in Global Context, edited by Gene L. Green, Stephen T. Pardue, and K. K. Yeo, 133-147. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2020.

Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti. “Christology in Africa: Search for Power.” In Christology: A Global Introduction -- An Ecumenical, International, and Contextual Perspective, 245–55. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2003. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Outlining various facets of Christology in Africa, Kärkkäinen draws primarily on the works of Nyamiti, Mbiti, Pénoukou, and Onaiyekan, focusing on models of Christ as ancestor, master of initiation, head of the family, and healer. He concludes the chapter illustrating challenges for African Christology today, namely balancing over-traditionalism in the contemporary climate with a need to maintain strong African roots.

Küster, Volker. “B. ‘But You, Who Do You Africans Say That I Am?’ Christology in the Context of African Tribal Cultures and Religions’.” In The Many Faces of Jesus Christ: Intercultural Christology, translated by John Bowden, 57–76. London: SCM, 2001. Export Item

Drawing upon pioneering male theologians, Küster identifies and analyses four models of African Christology: Jesus Christ the chief, master of initiation, ancestor, and healer. He further probes the ancestor image in the theologies of Charles Nyamiti and Bénézet Bujo. Translated from German, Die vielen Gesichter Jesu Christi. Christologie interkulturell. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1999.

Wessels, Anton. “The Black Christ, The African Christ, and Christ in Suriname.” In Images of Jesus: How Jesus Is Perceived and Portrayed in Non-European Cultures, translated by John Vriend, 83–115. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1990. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Wessels traces the turbulent history of Africans, particularly the slave trade with the consequent images of the ‘white’ and ‘black’ Christ in the United States and Southern Africa. He introduces the ‘African Christ’ by examining the cultural background, the history of Jesus’ proclamation and reception, and key christological titles: victor, chief, ancestor, and healer. The final section explains Christ in Suriname, demonstrating the inter-relatedness of African Christologies globally. Originally published as Jezus zien: hoe Jezus is overgeleverd in andere culturen. Baarn: Ten Have, 1986.

Anthologies

Twentieth-century African Christology emerged not with individual theologians publishing monographs, but with consultations of scholars examining the subject from various contexts and perspectives. The first such consultation, ‘Confessing Christ in Africa Today’, July 5-15, 1988, in Bossey, Switzerland, gathered African and African-descent scholars from Africa, Asia, Europe, the USA, and the Caribbean, and eventually generated an important anthology (Pobee 1992). In 1989, an ecumenical symposium of Eastern African theologians met in Kenya, producing a watershed publication on African Christology (Mugambi and Magesa 1989). Significantly, Christology was the first theological topic these theologians addressed within the African Christianity Series that followed. Schreiter 1991 assembled several essays from this 1989 publication, together with additional essays from francophone Western Africa, to expand the conversation across the continent. Abogunrin, Akao, and Akintunde 2003 then provided an array of christological reflections from West Africa, published by the Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies. More recently, the Africa Society of Evangelical Theology (ASET) convened in Kenya, with African and Africanist evangelicals offering far-ranging reflections on Christology in Reed and Ngaruiya 2021. These anthologies reflect key aspects of the emergence of African Christology including the rationale and methodological considerations, as well as central issues and themes in its development.

Abogunrin, Samuel O., J. O. Akao, and Dorcas O. Akintunde. Christology in African Context. Biblical Studies Series 2. Nigeria: Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, 2003. Export Item

This extensive work compiles almost thirty conference papers. Most essays apply Old or New Testament texts or topics to African contexts (e.g., vicarious sacrifice, suffering, scapegoatism). Other essays address perennial themes in Christology (e.g., the virgin birth, incarnation, atonement), while still others examine Christology in relation to contemporary issues in African Christianity (e.g., inculturation, ancestor veneration, women, and social praxis). While rich in content, accessibility is difficult.

Mugambi, Jesse N. K., and Laurenti Magesa. Jesus in African Christianity: Experimentation and Diversity in African Christology. African Christian Series. Nairobi: Initiatives, 1989. Export Item

The fruit of an ecumenical symposium of Eastern African theologians, this anthology provides foundational reading in African Christology. Acknowledging Christology as the central issue of Christian theology and exposing the paucity of African theological reflection on it, these theologians deliberate on the theological meaning of Christ within African Christianity. They examine “the specific significance of Christ as seen by Africans” (p. xi) in relation to African history, culture, and contextual realities.

Pobee, John S., ed. Exploring Afro-Christology. Studien Zur Interkulturellen Geschichte Des Christentums 79. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1992. Export Item

African and African-descent theologians from Africa, Asia, Europe, USA and the Caribbean innovatively consider how Africans articulate their experience of Jesus. Examining hermeneutical, biblical, and theological foundations, they consider Christ in relation to African religion, the oppressed, decolonising theology, and African instituted churches. They assert that “christologies emerging from Africa need to be assembled and engaged in dialogue between themselves as well as with the universal church” (p. 11).

Reed, Rodney L., and David K. Ngaruiya, eds. Who Do You Say That I Am?: Christology in Africa. ASET Series 6. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, 2021. Export Item

Within the Africa Society of Evangelical Theology Series, this volume contains twenty-five papers from the 2020 ASET conference in Karen, Nairobi. It provides a rich tapestry of current evangelical reflections from Africans and Africanists on the perennial questions of Christology. The three main parts reflect its comprehensiveness in scope: Christ in the Bible; Christ in Theology and Church History; and Christ in Praxis. The final part contains tributes to the late Professor John S. Mbiti.

Schreiter, Robert J, ed. Faces of Jesus in Africa. Faith and Culture Series. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Highlighting Africa’s significance as the fastest growing Christian continent, Schreiter presents “some of the faces of Jesus and how Africans today are responding to the Christ who encounters their cultures” (p. xiii). Eleven essays from francophone Western Africa and anglophone Eastern Africa, focusing on inculturation and liberation, reflect both the problems facing Christology in Africa as well as “the stunning contributions it is making to the world church” (p. ix).

Bibliographies

The following section includes three bibliographies on African Christology, produced at different times and from various contexts. Janssen and Gerhardt 1990 contains a section of references on Christology in Africa among other geographical regions. Conradie and Fredericks 2004 includes an excellent bibliography entitled ‘Doctrine of Christ’. Finally, Atansi et al. 2023 provides a comprehensive catalogue of sources relating to African Christology over the past century, referencing over 500 items.

Atansi, Chukwuemeka A., Joshua Robert Barron, Peter R. K. Bussey, Samuel K. Bussey, David M. M. Lewis, Yoel Koster, William Mbuluku, and Diane Stinton. “Christology.” Collaborative Bibliography of African Theology. Accessed October 30, 2023. URL: Link Access: Export Item

This recent bibliography, though not exhaustive, is an attempt to compile a thorough list of sources related to African Christology, both formal and informal, over the past century. It provides over 500 items in one alphabetical list, with most entries in English and a few in other European languages (e.g., French, German, Italian, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish) or African languages (Igbo, Twi, Kiswahili).

Conradie, Ernst, and Charl E. Fredericks, eds. “Doctrine of Christ.” In Mapping Systematic Theology in Africa: An Indexed Bibliography, 108–17. Stellenbosch: Sun Press, 2004. URL: Link Access: Export Item

This work contains a 10-page bibliography entitled ‘Doctrine of Christ’ (pp. 108-117) with a lengthier list of ‘general’ works (pp. 108-114), followed by a number of sub-headings listing works in several categories including ‘Atonement’, ‘Cross’, ‘Incarnation’, and ‘Resurrection’ (pp. 114-117).

Janssen, Hermann, and Angrit Gerhardt. Bibliography on Christology in Africa, Asia-Pacific and Latin America. Theology in Context Supplements 5. Aachen: Institute of Missiology, 1990. Export Item

Janssen and Gerhardt compile bibliographical references to christological works from three geographical regions that were available at the time of publication in the library of the Institute of Missiology Missio, Aachen. The section on Africa comprises 8 pages of works in English, French, and German (pp. 1-8).

Textbooks

Although there is not yet an explicit textbook in African Christology, the following works may serve this purpose. Each text seeks to introduce and assess current developments in the field, placing the expressed Christologies within their historical and theological context and outlining their significance to local and global Christianity. Mbogu 2012 conducts in-depth textual analysis while Stinton 2004, Ezigbo 2010, and Clarke 2011 also incorporate field research, offering empirical evidence of African Christologies within selected contexts and church traditions.

Clarke, Clifton R. African Christology: Jesus in Post-Missionary African Christianity. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2011. Export Item

Clarke examines Christology from the perspective of African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in Ghana, analysing language and symbols that reflect their worldviews and daily experiences. His exploration of the meaning of Jesus’ identity and work reveals the theological significance of faith in the Christ-event both locally and globally. It also elucidates the practical relevance of Christology for “the working of aspects of society . . . and the capacity for [African] self-definition” (p. 2).

Ezigbo, Victor I. Re-Imagining African Christologies: Conversing with the Interpretations and Appropriations of Jesus Christ in African Christianity. Princeton Theological Monograph Series 132. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2010. Export Item

Ezigbo critiques the ‘solution-oriented Christologies’ of African theologians and laypeople, proposing instead a contextual Christology that interprets the Christ-event as simultaneously “a question and an answer to the theological, cultural, religious, anthropological, spiritual, and economic issues” within African contexts (p. xiii). Utilising field research on grassroots Christologies in Nigeria, Ezigbo constructs a ‘Revealer Christology’ that explicates Jesus’ identity, meaning, and significance in communicating, mediating, and interpreting both divinity and humanity.

Mbogu, Nicholas Ibeawuchi. Jesus in Post-Missionary Africa: Issues and Questions in African Contextual Christology. Enugu: San Press, 2012. Export Item

Mbogu considers pertinent christological themes from African perspectives including the fundamental belief that God became human; the confession of Jesus as fully God and fully human; and the universality of Jesus’ saving event. Mbogu situates these themes within wider Christian tradition, then offers an African interpretation of their meaning and significance. He thereby shows that Christ remains a living subject of faith and life in a post-missionary African society.

Stinton, Diane B. Jesus of Africa: Voices of Contemporary African Christology. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004. Export Item

In this groundbreaking work, Stinton explores African Christologies by integrating textual and qualitative research among French- and English-speaking theologians, clergy, and laity. These Christologies are articulated “not only in light of biblical revelation and Christian tradition but also in terms of African realities both past and present” (p. 21). Findings include four inter-related categories: Jesus as life-giver, mediator, loved one, and leader, and conclusions affirm their significance for African and world Christianity. Co-published by Paulines Publications Africa: Nairobi, 2004.

Primary Resources Online

From the outset of modern African theology in the mid-twentieth century, theologians have affirmed the validity and significance of ‘oral’, ‘implicit’, ‘informal’, or ‘lived’ Christologies. That is, African Christology is not limited to formal, theological publications, but also incorporates the manifold expressions of believers’ understanding and experience of Jesus within the realities of everyday life. The items below are but illustrative of the multiplicity of creative, dynamic reflections on Christ in worship, song, dance, preaching, poetry, painting, sculpture, textile arts, film, etc. These christological expressions warrant serious attention since they form the substructure which helps generate formal, written Christologies. Significantly, these informal Christologies reflect the myriad of ways in which Jesus becomes incarnate or dwells among African peoples in their diverse cultures, churches, and life experiences. Some of them also engage the socio-political issues of the day, offering a deeper understanding and, at times, prophetic critique of certain aspects of African life, such as ethnic hostilities, economic exploitation, gender oppression, corruption, and the abuse of power. Whether using traditional indigenous art forms or contemporary globalised technology, like music videos on the internet, these christologies manifest the dynamic ways in which Jesus enters African believers’ lives from generation to generation, with significance for local and world Christianity.

Adeboye, Enoch A. Jesus. Sermon video, 8:00:30. Given at the Holy Ghost Service, Redemption Camp, Ogun State, Nigeria, 3 June, 2022. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Adeboye preaches “Jesus: The Origin,” from John 1:1, 14. Throughout the sermon (5:15:00 – 6:51:00), he repeatedly urges the congregation to shout ‘Jesus!’ to dispel the devil and to declare the all-powerful name of Jesus. Breaking into chorus (“That Wonderful Name, Jesus”) and narrating stories and testimonies, Adeboye proclaims that since Jesus is the origin of everything, he alone can rectify every imperfection in life (e.g., illness, debt, sorrow) and overcome every evil power.

Dornford-May, Mark, dir. Son of Man. Spier Films, 2006. URL: Link Access: Export Item

In this award-winning production, British-born, South African director Mark Dornford-May retells the story of Jesus in a present-day, fictionalised ‘Judea’ within Southern Africa. The Gospel narrative takes on distinct African expression with an all-African cast speaking (primarily) Xhosa, local rural and urban scenes, and traditional choral music. The highly politicised and culturally integrative content renders an African interpretation of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection that resonates with local and international audiences.

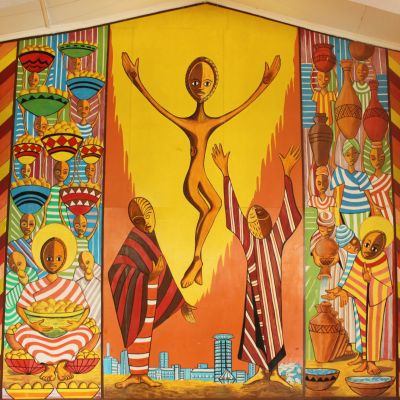

Jesus Mafa. Zaccheus Welcomes Jesus. 1973. Painting. Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Vie de Jesus Mafa (Life of Jesus Mafa) is a series of over seventy paintings depicting the life and parables of Jesus as an African man in a local village. French Catholic missionary François Vidil worked with the Mafa Christian community in Cameroon to produce these images with the aim of discovering and communicating the reality of Christ incarnate within everyday life in Africa. (Follow the link and select the country link ‘Cameroon’ to see more paintings.)

Julian, Nakie. Tukutendereza Yesu Luganda New 2015 Lyrics. Worship music audio, 4:41. Shield of Faith. Posted 25 April, 2015. URL: Link Access: Export Item

“Tukutendereza Yesu” (“We praise you Jesus”) is a Luganda hymn that became the theme song of the Balokole Revival. Emerging in the 1920s and 1930s in Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda, this revival spread throughout East Africa fostering renewal in Anglican and other Protestant churches. At the heart of this large-scale renewal movement is the call for a deeper experience of salvation through the blood of Christ.

Kuma, Afua. Jesus of the Deep Forest: Prayers and Praises of Afua Kuma. Translated by John Kirby. Accra: Asempa Publishers, 1981. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Kuma’s extemporaneous, vernacular (Twi) prayers and praises express her adoration of Jesus in the thought-forms and worldview of her Akan people in rural Ghana. Adapting the cultural format and honorifics for praising traditional chiefs to worship Christ, Kuma interweaves striking local imagery together with biblical allusions to depict Jesus as Lord over all, as protector, provider, and victor over evil, among other themes spanning creation, redemption, and eschatology. Originally published as: Kwaebirentuw ase Yesu: Afua Kuma ayeyi ne mpaebo̳. Accra: Asempa Publishers 1980.

Lonardi, Matteo. Artist Portrait: Elimo Njau. Video portrait, 6:00. Haus der Kunst and Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute. Posted 26 October, 2020. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Originally from Tanzania, Njau is a leading Kenyan artist. Within this video, Njau reflects on his mural paintings in the Anglican cathedral of Murang’a, undertaken between 1956 and 1959 during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. In five, twelve by fifteen feet murals, he depicts key moments in the life of Christ (nativity, baptism, Last Supper, Gethsemane, and crucifixion), reflecting local landscapes, peoples, and historical realities.

Mveng, Englebert. Stations of the Cross and Resurrection. 1962. Photographs of paintings in the chapel of Hekima University College, Nairobi, Kenya. Flickr. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Mveng was a Jesuit priest, a prominent Cameroonian historian and theologian, and an internationally renowned artist. This series of paintings adorns the chapel of Hekima College, Nairobi. Using simple lines, symbolic colours, and distinctive, stylised designs, Mveng portrayed Jesus as an African Christ within African scenes. The paintings clearly depict both the intimate immanence of Jesus in the fourteen “Stations of the Cross” and his radiant transcendence in the “Resurrection.” (The latter was designed by Mveng and painted by the Sudanese artist Stephen Lobalu).

Njeri, Eunice. Bwana Yesu. Music video, 7:33. Princecam Media. Posted 12 July, 2012. URL: Link Access: Export Item

In lyrics and filming, Njeri’s music video (with 5.7M views) depicts African women’s lived experience of ‘Bwana Yesu’ (‘Lord Jesus’) as the all-sufficient provider within the realities of everyday life. In contexts of poverty, gender oppression, and domestic violence, women find intimacy and personal transformation in Christ as ‘my hope’, ‘welcome help’, and ‘saviour’ who ‘died for me’ and ‘washed away all my sins’, bringing joy and hope.

Onwenu, Onyeka. Onye bu Nwanne m? Music video, 3:59. Akin Alabi Films. Posted 9 April, 2013. URL: Link Access: Export Item

A popular contemporary Nigerian musician, Onwenu celebrates Christ as Nwanne m (‘child of my mother’). Celebrating and appropriating Christ as my brother and/or sister is Onwenu’s way of valorising the reality and significance of the incarnation. This fundamental event and the ongoing actuality of God’s unity with humanity in Christ enable believers to counter any form of exclusion based on (mis)understandings of Christ’s identity.

Setiloane, Gabriel. “I Am an African.” Pro Veritate 9, no. 8 (December 15, 1970): 8–9. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Setiloane’s poem conveys the historical transmission of the gospel and theological interpretation of Jesus in South Africa. Inculturation and liberationist perspectives cohere: the “pale” child the “White Man” brought “eludes us still,” whereas the “Sunburnt Son of the Desert” would have been recognised. Yet, “it is when he is on the cross,” depicted in local sacrificial imagery, he makes peace “with God, our fathers and us,” and “with all mankind.”

Biblical Christologies

In one sense, every Christology is biblical since the Bible is the primary revelation of Jesus Christ. Certainly, African Christians have reflected on the biblical revelation of Christ ever since the gospel reached their continent. More recently, from the outset of modern African theology in the twentieth century, theologians have underscored the Bible as the fundamental pillar or source of African Christology. Yet christological expressions vary in the relative weighting of explicit biblical sources in relation to other source materials, including Christian tradition, African worldviews and thought-forms, the living church, and African realities. This section offers examples of African Christologies in which biblical analysis and reflection feature significantly. Two main approaches may be discerned. Some theologians find points of departure in the Bible and move to the African context to elaborate christological themes (e.g., Mbiti 1973, Ukpong 1992, Bayinsana 1996, Abogunrin 1998). Others highlight African realities as the locus for biblical reflection (e.g., Dube 2008, Aarbakke 2019). These movements are fluid, not fixed, and together they reflect both the role of scripture in Africans’ attempts to understand and experience Christ, and the christological contributions of those interpreting Jesus from African perspectives.

Aarbakke, Harald. The Eldest Brother and New Testament Christology. Bible and Theology in Africa 27. New York: Peter Lang, 2019. Export Item

Norwegian scholar Aarbakke examines the image of Jesus as the eldest brother, advocated by Anthony Nkwoka, Harry Sawyerr, and François Kabasélé Lumbala. Outlining their views on the status and various roles of the eldest brother, Aarbakke adds an ethnographic survey to further clarify the concept. He then establishes an exegetical basis for understanding this christological image from several New Testament texts, thereby confirming the image as a meaningful African Christology.

Abogunrin, Samuel O. “The Lucan View of Jesus Christ as the Savior of the World from the African Perspective.” Journal of Religious Thought 54/55, no. 2/1 (Spring-Fall 1998): 27–43. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Abogunrin elaborates the Lucan view of sōtēria (salvation) in light of indigenous Yoruba concepts and certain deficiencies within missionary preaching of the gospel. He demonstrates the holistic and comprehensive nature of Jesus as Saviour of the world, in terms of humanity and society’s total well-being, and its universal significance. He then concludes with implications for gospel proclamation in Africa in relation to religious pluralism and prophetic witness.

Bayinsana, Eugene. “Christ as Reconciler in Pauline Theology and in Contemporary Rwanda.” Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology 15, no. 1 (1996): 19–28. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Bayinsana exemplifies biblical scholarship in close dialogue with African realities. Writing shortly after the 1994 Rwandan genocide, he expounds Christ as reconciler in Pauline theology, elaborating on both the vertical and horizontal dimensions of reconciliation with God and humanity. He then analyses factors contributing to the genocide, and despite the cost entailed, calls for Tutsi and Hutu Christians to embrace reconciliation in Christ, while attending to issues of justice.

Dube, Musa W. “Talitha Cum! A Postcolonial Feminist HIV & AIDS Reading of Mark 5:21-43.” In The HIV & AIDS Bible: Selected Essays, 77–98. Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 2008. Export Item

Dube offers a deeply contextual reading of Mark 5:21-43 from “the multiple levels of postcolonial, feminist, and HIV & AIDS perspectives” (p. 77). Her narrative analysis is not explicitly christological, examining all the main characters involved; however, she highlights “the character of Jesus” (p. 82) as “the main actor” (p. 83), who is “the healer, the liberator” (p. 87) in situations of gender, imperial, and HIV & AIDS oppression.

Mbiti, John S. “‘ὁ Σωτὴρ Ἡμῶν’ [Our Saviour] as an African Experience.” In Christ and Spirit in the New Testament, edited by Barnabus Lindars and Stephen S. Smalley, 397–414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. Export Item

Mbiti, an early, distinguished African biblical scholar, examines the concept of Saviour in the New Testament, in African tradition, and in African Christianity. Despite its scarcity within the NT, Mbiti deems it the most pervasive and meaningful christological title to African Christians. With salvation understood primarily as physical protection and well-being, Mbiti concludes it “has eclipsed the centrality of sin and the work of atonement as wrought by Christ” (p. 411).

Mbuvi, Andrew M. “Christology and Cultus in 1 Peter: An African (Kenyan) Appraisal.” In Jesus Without Borders: Christology in the Majority World, 141–61. Majority World Theology Series. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2014. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Mbuvi notes 1 Peter’s use of strong cultic language and images (sacrifice, temple, priesthood) to present Christ, questioning how these shaped the Petrine community’s understanding of Jesus and how the Petrine perspective related to Chalcedonian Christology. He analyses 1 Peter’s cultic language in light of select pre-Christian cultic practices of the Akamba people of Kenya, demonstrating how African interpretations can enhance “the common Western readings” (p. 159) of Christology. Republished in Majority World Theology: Christian Doctrine in Global Context, edited by Gene L. Green, Stephen T. Pardue, and K. K. Yeo, 201-213. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2020.

Nyende, Peter Thomas Naliaka. “Jesus, the Greatest Ancestor: A Typology-Based Theological Interpretation of Hebrews’ Christology in Africa.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2006. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Convinced that the Bible is fundamental to Christian faith and imperative to African theology, Nyende interprets the Christology of Hebrews theologically in relation to typology. Just as Hebrews presents Jesus as superior to any Jewish mediatorial figures (e.g., angels, Moses, the Aaronic priesthood), so he is superior to African ancestors. Thus, Jesus is the definitive mediatorial figure or the ‘greatest ancestor’, with implications for faith and practice within African Christianity.

Okure, Teresa. “Jesus and the Samaritan Woman (Jn 1:1-42) in Africa.” Theological Studies 70, no. 2 (June 2009): 401–18. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Okure considers Jesus and the Samaritan woman from an African perspective, focusing on what the two share in common from their own contexts of “rejection, prejudice, and isolation” (p. 409), and how these relate to African experience. Using a narrative and intertextual method, Okure transports them to an African audience to challenge the inherited barriers of racism and sexism that keep African Christians from confessing Jesus as the universal saviour.

Ukpong, Justin S. “The Immanuel Christology of Matthew 25:31-46 in African Context.” In Exploring Afro-Christology, edited by John S. Pobee, 55–64. Studien Zur Interkulturellen Geschichte Des Christentums 79. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1992. Export Item

A pioneer of African biblical scholarship, Ukpong poses the christological question of Jesus’ identity and presence in Africa today. Drawing from Matthew 25:31-46, Ukpong ascertains ‘God with us’ or ‘Immanuel Christology’ as the framework of Matthew’s Christology. He highlights ‘the least of my brethren’ with whom Jesus identifies, concluding that Jesus’ identity and significance in Africa are defined by those less fortunate (the hungry, sick, prisoners etc.).

Umoren, Anthony Iffen. Paul and Power Christology: Exegesis and Theology of Romans 1:3-4 in Relation to Popular Power Christology in an African Context. New Testament Studies in Contextual Exegesis 4. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2008. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Umoren creates an ‘inculturational interface’ (p. vii) between Paul’s power Christology, established exegetically and theologically from Rom. 1:3-4, and power Christology as examined ethnographically among Christians in Abuja, Nigeria. Against widespread beliefs and practices informed by African Religion and prosperity gospel claims about Jesus as power, Umoren demonstrates biblically that Christ becomes both ontologically and functionally the power of God for salvation. Conclusions outline implications for African Christianity.

Doctrinal Christologies

This section includes christological reflections that focus on fundamental beliefs about Christ and the whole of the Christ-event, that is, his incarnation, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension. These beliefs have come to be known as the classical, traditional or ‘universal’ truths about the identity and work of Christ. In the context of African Christianity, doctrinal Christologies articulate the conditions of possibility and contents of such beliefs in the light of African religious, cultural, and social worldviews, including the human experiences and conditions of people in Africa. Examples here include reflections on his incarnation (Okolo 1978a; Okesson 2003; Magezi and Magezi 2017); the two natures of Christ (Oduyoye 2001; Nwaogaidu 2016); the humanity of Christ (Ng’Weshemi 2002); and his suffering (Nwatu 1997). These Christologies go beyond classical formulations to discern and delineate how Christ continues to be present and active on the continent. Moreover, some of the expressions that are rendered in African mother tongues and idioms are crucial for gaining fresh insights into the doctrine of Christ.

Abogunrin, Samuel O. “The Total Adequacy of Christ in the African Context.” Ogbomosho Journal of Theology 1, no. 1 (1986): 1–16. Export Item

Abogunrin examines some christological themes in the Letter to the Colossians in the light of contemporary African realities. More specifically, he draws parallels between the Colossian heresy and certain expressions of African Christianity, particularly with regard to the blending of Christianity and African religion. Abogunrin argues that the uniqueness of Christ must be upheld and preached so that Christians do not worship angels or idols, but rather Christ alone.

Magezi, Vhumani, and Christopher Magezi. “Christ Also Ours in Africa: A Consideration of Torrance’s Incarnational, Christological Model as Nexus for Christ’s Identification with African Christians.” Verbum et Ecclesia 38, no. 1 (2017): 1–12. DOI: 10.4102/VE.V38I1.1679 Access: Export Item

Acknowledging the perception of Christ’s foreignness within African Christianity, Magezi and Magezi seek out alternative christological models for the African context. They assess Torrance’s incarnational christological model, particularly his ideas of anhypostasis and enhypostasis. They conclude that Torrance’s incarnational model of Christology is useful as it demonstrates the universality of the gospel message for humanity in Christ’s conquest over sin. African Christians can therefore claim Christ as ‘ours’.

Maimela, Simon S. “The Atonement in the Context of Liberation Theology.” International Review of Mission 75, no. 299 (1986): 261–69. DOI: 10.1111/j.1758-6631.1986.tb01479.x Access: Export Item

Maimela examines atonement theology through the lens of liberation theology. He outlines Aulen’s three categories of atonement theory: ransom theory, satisfaction theory, and moralistic theory, concluding that these are generally unattractive to liberation theology. Ransom theory, however, holds the most promise (cf. Cone). Maimela argues that atonement theory must address both sin and its consequences, namely injustice. He concludes that liberation theology offers a more comprehensive vision of Christ’s salvation.

Mushete, Alphonse N. “The Figure of Jesus in African Theology.” Edited by Christian Duquoc and Casiano Floristan. Concilium, Christian Identity, 196 (April 1988): 73–79. Export Item

Mushete argues that African Christology is becoming increasingly responsive to African cultures. Examining the vitality of African traditions, Mushete observes the ‘continuing domination’ of racism and neo-colonialism in Africa. He subsequently examines the anthropological foundations of African Christology, outlining facets of African worldviews. Finally, Mushete examines christological language, reflecting on the images of Christ as chief and supreme ancestor, demonstrating how Christologies offer an account of the unique contribution of African cultures.

Ng’Weshemi, Andrea M. Rediscovering the Human: The Quest for a Christo-Theological Anthropology in Africa. Studies in Biblical Literature 39. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2002. Export Item

Ng’Weshemi begins by examining humanity in African tradition and in the post-colonial African context. Seeking to learn from Africa’s past, he draws from Nyerere’s African socialism and Ela’s African liberation theology. Ng’Weshemi examines anthropology and Christology in the work of Barth and Rahner, developing insights relating to Africa. He examines images of Christ as ancestor and liberator-brother, concluding that theological anthropology in Africa is communitarian, christological, liberative, and holistic.

Nwaogaidu, John Chidubem. Jesus Christ - Truly God and Truly Man: Towards a Systematic Dialogue between Christology in Africa and Pope Benedict XVI’s Christological Conception. African Theology 3. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2016. Export Item

Nwaogaidu argues that the incarnate Christ must be seen as both ‘truly God and truly man’ in the African context. In bringing together African Christology and the Christology of Pope Benedict XVI, Nwaogaidu interprets Christ in a way that allows African Christians to encounter and experience the reality of Christ and his saving work through the contextualisation of the gospel in Africa.

Nwatu, Felix. “The Cross: Symbol of Hope for Suffering Humanity.” African Ecclesial Review 39, no. 1 (1997): 2–17. Export Item

Nwatu examines the cross in historical context, outlining its pre-Christian and early Christian uses from Plato to Constantine. He helpfully distinguishes sign from symbol, arguing that the cross is not a mere sign, but a symbol replete with meaning through Christ. Nwatu outlines the connection between the cross and suffering, arguing that African Christians should learn from the crucified Christ. He concludes that the cross is a symbol of hope and unity.

Oduyoye, Mercy A. “Jesus the Divine-Human: Christology.” In Introducing African Women’s Theology, 51–65. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. URL: Link Access: Export Item

For Oduyoye, the visitation of Mary and Elizabeth symbolises African women’s Christology: women bearing witness together to their encounters with Jesus in daily life within their communities. Integrating several women’s meetings with Jesus, including her own, she elaborates Christology primarily in relation to soteriology and the quest for life inherent in African Religion. Contributions highlight Jesus as suffering in solidarity and comradery, and victoriously liberating women within “life-denying and life-threatening contexts” (p. 63).

Okesson, Gregg A. “The Incarnation of Jesus Christ as a Hermeneutic for Understanding the Providence of God in an African Perspective.” Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology 22, no. 1 (2003): 51–71. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Okesson examines the providence of God from traditional theological perspectives while questioning its meaning and significance within African experience. He argues for a hermeneutic of understanding God’s involvement in the world in the Incarnation, which vividly demonstrates the “nearness of God” (p. 61). From an African perspective, this truth must be ‘liveable’ in the concrete realities of life, with implications for grasping Christ’s humanity, theological anthropology, theodicy, and human responsibility.

Okolo, Cukwudum Barnabas. “Christ, Emmanuel: An African Inquiry.” African Ecclesial Review 20, no. 3 (1978): 130–39. Export Item

Okolo argues for the incarnation of Christianity in African cultures, pointing to the image of Christ as Emmanuel in Africa. Christ must be truly indigenised, becoming an African Emmanuel, who dwells with Africans and takes on their cultural imagery and customs. In the wake of colonialism and Western missionary activity, this indigenisation is all the more important in order to avoid a ‘screen’ coming between Africans and Christ.

Trends in African Christologies

Scholars observe certain difficulties in clearly distinguishing trends in African Christologies. Julius Gathogo, for example, claims there are nine christological approaches: contextualisation, indigenisation, rebirth, inculturation, renewal, rejuvenation, renaissance, liberation, and reconstruction. Conventionally, however, African Christologies have mainly been interpreted in relation to three major trends: the first is inculturation Christology, which is sometimes labelled intercultural Christology, the second is liberation Christology, which is also rendered black Christology, and the third is reconstruction Christology (Atansi 2020a – see ‘Christology and Social Transformation in Africa’). Although there is considerable overlap among the various trends, debates continue regarding the compatibility of their respective methodological approaches, claims, and purposes. The intent of this section is not to explore such debates but rather to introduce these three core trends – inculturation and intercultural, black and liberation, and reconstruction – and how the figure of Christ is appropriated within each approach.

Inculturation and Intercultural Christologies

Inculturation is one of the three main trends in African Christologies. Considered to lie at the heart of African Christologies, it was the foremost concern in the christological works of many pioneer African theologians (e.g., Okolo 1993, Mugambi and Magesa 1989 – see ‘Anthologies’). In this trend, the identity and work of Christ are interpreted in light of African languages, worldviews, images, and cultural traditions. Christological elements from these indigenous sources are brought into dialogue with insights from the conventional sources of Christology, such as scripture and creedal formulations, to (re)present the person and mission of Christ. Two main methodological approaches can be identified in the inculturation trend. The first approach begins by examining scriptural and creedal data about Christ which correspond with christological elements found in African traditional sources. The second approach begins by identifying and describing christological elements evident within the African cultural and religious heritage and relating these to various expressions of Christology in the so-called classical Christian sources.

Related to inculturation are what some contemporary scholars have described as intercultural Christologies (e.g., Hearne 1980, Küster 2001 – see ‘African Christianity within Global Surveys’). These Christologies demonstrate how the encounters among diverse cultures shape their respective understandings of Jesus Christ. In this case, particular expressions of African Christology become clarified and enhanced through their interaction with other African and non-African cultures. This intercultural approach to Christology is marked by an ‘openness’ to other cultures (Hearne 1980). The aim is to learn how Christ is appropriated in other cultures and for this experience to enrich one’s knowledge of Christ within one’s own particular culture.

Bahemuka, Judith M. “The Hidden Christ in African Traditional Religion.” In Jesus in African Christianity: Experimentation and Diversity in African Christology, edited by Jesse N. K. Mugambi and Laurenti Magesa, 1–16. Nairobi: Initiatives, 1989. Export Item

Bahemuka’s thesis is that Christ has been and is present in African traditional religion. This christological understanding is in line with the fundamental theological idea of logos spermatikos, which upholds that Christ pervades all cultures from the beginning. In this view, the task of inculturating faith in Christ in Africa consists not just in cultural translation of the Christian understandings of Christ, but in uncovering elements of the ‘Christic’ presence in African traditional religion.

Bediako, Kwame. Jesus and the Gospel in Africa: History and Experience. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004. Export Item

Bediako offers an account of the African experience of Christ in both the African religious-cultural heritage and in the gospel. This text is considered a good example of inculturation Christology in practice. Bediako leads us to appreciate that one of the goals of inculturation Christologies is the mutual enrichment of both African culture and the Christian message – an enrichment that is effected by the experience of Christ in both spheres.

Bujo, Bénézet. African Theology in Its Social Context. Translated by John O’Donohue. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1992. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Bujo demonstrates the praxis of inculturation and intercultural Christologies. First published in German, the work is undoubtedly inspired by Bujo’s experience of teaching in Europe as he takes an intercultural approach in offering a socio-theological account of Christ in Africa. He draws primarily on the traditional African image of ancestor to interpret the identity and work of Christ as ‘proto-ancestor’, employing this Christology in engaging perplexing social issues in Africa.

Ebebe, Cosmas Okechukwu. “Who Do You Say I Am? John Mbiti, Ukachukwu Chris Manus, Charles Nyamiti and Bénézet Bujo’s Approaches to Christology.” PhD diss., Pontificia Universitas Gregoriana, 2009. Export Item

Ebebe offers a detailed exploration of the various approaches of inculturation Christologies. He examines the works of key African theologians including Manus, Nyamiti, and Bujo, who are known for their contributions in the task of inculturating Christ. Despite their different approaches, Ebebe argues that their goal was the same: to shed further light on the mystery of Christ and to enrich the understanding of his identity and work.

Hearne, Brian. “Christology and Inculturation.” African Ecclesial Review 22, no. 6 (1980): 335–41. Export Item

Hearne asserts that Christology is at the heart of any authentic practice of inculturating faith in Africa or elsewhere. The starting point lies in the mystery of Christ’s person and work, which is revealed in his humanity and becomes further known through studying his earthly life and resurrection in relation to the local context. The goal of inculturation, therefore, is to lead people to a loving encounter with Jesus.

Nwaigbo, Ferdinand. “Understanding Inculturation in the Light of the Resurrection.” African Ecclesial Review 43, no. 1–2 (2001): 41–55. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Nwaigbo introduces inculturation Christology as the ‘paschal process’ of exploring the relationship between the Christian message about Christ and its resonance in African culture. In the light of this understanding, he then asks: “How is Jesus’ Resurrection related to African culture?” (p. 40). His response draws on the value of life, which is a central motif in both African and Christian worldviews.

Nyamiti, Charles. “Christ’s Ministry in the Light of African Tribal Initiation Ritual.” African Christian Studies 3, no. 1 (1987): 65–87. Export Item

In African traditional societies, there are processes of initiation associated with stages of life and life’s attainments, such as birth, the transition into adolescence and adulthood, etc. Nyamiti employs this cultural framework for interpreting the ministry of Christ, understood as progressing through the stages of birth, entry into adulthood, passion, suffering, death, resurrection, ascension into heaven, and eternal reign in glory.

Okolo, Cukwudum Barnabas. “Inculturation and the African Soul: Towards African Christology.” African Christian Studies 9, no. 3 (1993): 3–13. Export Item

Okolo views the nature and mission of African Christology as an inculturation project. This project consists in rediscovering the positive elements in African cultural and religious traditions and transforming them in the light of the mystery of Christ. These elements, in turn, shed light on the meaning and significance of Christ in African religious and cultural landscapes.

Udoh, Enyi Ben. Guest Christology: An Interpretative View of the Christological Problem in Africa. Studies in the Intercultural History of Christianity 59. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1988. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Guest Christology is another example of inculturation Christology. It reflects on the view that “Jesus Christ is first and foremost a guest in Africa” (p. 13). The image draws upon the natural experience of African hospitality and open-heartedness. Udoh adopts this guest image to address the problem of Christ’s presence in Africa and to show how Christ is seen as one who is at home in Africa.

Ukpong, Justin S. “Christology and Inculturation: A New Testament Perspective.” In Paths of African Theology, edited by Rosino Gibellini, 40–61. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994. Export Item

Ukpong outlines biblical foundations for African inculturation Christology. Drawing on New Testament passages, he argues that inculturation is not an attempt to make Christ meaningful to Africans alone. Rather, Christologies throughout the ages have sought to represent (or inculturate) Christ’s identity and mission in terms accessible within different religious and cultural traditions. This effort is proper to the commission of Christ to his disciples – “go ye to all nations” (Matt. 28:16).

Liberation and Black Christologies

Liberation and black Christologies in the African context initially arose in the 1970s and 1980s. African theologians were inspired by Latin American liberation theology to highlight their own contexts of oppression and the longing for Christ’s liberation. Much of the literature in this section emerged in the 1970s during apartheid, a particular context of racial oppression within South Africa. These works span the periods of mid and late apartheid (Mofokeng 1983; Okolo 1978b), the end of apartheid (Maluleke 1994 & 1997), and post-apartheid in the twenty-first century (Urbaniak 2016 & 2019). There are other works which emerged from other African contexts (Éla 1994a & 1994b; Lushombo 2017), including the African Christian diaspora (Chike 2008). Significant also are reflections from the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians that was founded by Mercy Amba Oduyoye and first launched in Ghana in 1989. ‘The Circle’ shed light on the yearning for the liberation Christ won for all, with special focus on women in Africa. Together these christological reflections highlight the historical, cultural, religious, racial, socio-economic and gendered oppression of African peoples. They seek to unmask the root causes of the oppression, and to assess these in the light of Christ’s identification with the oppressed and the experience of his liberating power.

Chike, Chigor. “Proudly African, Proudly Christian: The Roots of Christologies in the African Worldview.” Black Theology 6, no. 2 (May 2008): 221–40. DOI: 10.1558/blth2008v6i2.221 Access: Export Item

Chike argues that Africans have retained their pre-Christian worldview in expressing their Christianity. After outlining characteristics of African traditional thinking, he focuses on three African images of Christ: victor, healer, and provider. Through his research, Chike shows that African Christians in the UK refer to these three images more often than white Europeans do. He concludes that contemporary African believers have learned to be both proudly African and proudly Christian.

Éla, Jean-Marc. “Christianity and Liberation in Africa.” In Paths of African Theology, by Rosino Gibellini, 136–53. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Éla identifies the marginalisation of the poor as a key challenge to African Christianity. He argues that evangelisation in Africa must no longer appear unconcerned about exploitation and that the Bible must be read from the perspective of the oppressed, identifying them with the crucified Christ. Finally, Éla contends that a credible Christianity in Africa must be one of “dirty hands” (p. 152), struggling for the liberation of ordinary people.

Éla, Jean-Marc. “The Memory of the African People and the Cross of Christ.” In The Scandal of a Crucified World: Perspectives on the Cross and Suffering, edited and translated by Yacob Tesfai, 17–35. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Arguing that African Christologies must be reinterpreted, Éla highlights two problems: the ‘dead-ends of ethnotheology’ (conflating Christ with ancestral cultures, producing images of chief, ancestor, healer) and the history of Western domination in Africa via the transatlantic slave-trade. Understanding black experience as the theological locus for reading the passion narrative, Éla contends that African Christology must return to the cross and Christ’s suffering to emphasise the gospel’s liberating message.

Lushombo, Léocadie Wabo. “Christological Foundations for Political Participations: Women in the Global South Building Agency as Risen Beings.” Political Theology 18, no. 5 (2017): 199–220. DOI: 10.1080/1462317X.2016.1195592 URL: Link Access: Export Item

Drawing from Sobrino and Mveng, Lushombo seeks to establish a “social ethics of participation” (p. 399) for those marginalised by unjust systems. Building upon Sobrino’s foundation, she examines Mveng’s concept of anthropological poverty to emphasise victims’ agency. Lushombo then turns to the concept of Ubuntu, demonstrating it to be a liberative concept for victims. She concludes that women victims have the ability to live as risen beings, using examples from the DRC.

Maluleke, Tinyiko Sam. “Christ in Africa: The Influence of Multi-Culturality on the Experience of Christ.” Journal of Black Theology in South Africa 8, no. 1 (May 1994): 49–64. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Maluleke argues that an African experience of Christ must flow from indigenous culture, thereby producing valid African Christologies. He contends that black and white Africans in post-apartheid South Africa must formulate their own Christologies whilst engaging one another. Lastly, he addresses multi-culturality, maintaining that this concept facilitates Western hegemony. He concludes that Africa “must be taken seriously as a valid and creative ‘host’ of Christ” (p. 61).

Maluleke, Tinyiko Sam. “Will Jesus Ever Be the Same Again: What Are the Africans Doing to Him?” Journal of Black Theology in South Africa 11, no. 1 (1997): 13–30. Export Item

Asking the christological title question vis-à-vis African appropriations of Jesus, Maluleke demonstrates that such appropriations are necessary for contextualising the gospel in Africa. In contrast to colonial images of Jesus, Maluleke emphasises the creativity of African expressions in grassroots Christologies, for example in poetry, sermons, and songs. Drawing from Wessels’ work, he illustrates the validity of two dominant images within African Christology: the suffering Christ and the African Christ.

Mofokeng, Takatso A. The Crucified among the Crossbearers: Towards a Black Christology. Kampen: Uitgeversmaatschappij J. H. Kok, 1983. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Mofokeng responds to the work of Barth and Sobrino in his articulation of a liberative, black Christology from the context of apartheid South Africa. Beginning with black consciousness, Mofokeng draws from liberation theology to formulate a historical Christology. Drawing on Barth’s Christology and Sobrino’s praxis of liberation, Mofokeng argues that black South Africans, as an oppressed people, must develop a liberative black Christology centred on the cross.

Okolo, Cukwudum Barnabas. “Christ Is Black.” In African Christian Spirituality, edited by Aylward Shorter, 68–71. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1978. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Writing in the South African setting of apartheid, Okolo presents black theology as a situational, liberative theology. Drawing from Cone as well as Latin American theologians Gutierrez and Bonino, Okolo argues that Third World Christianity has an inherent need for a decisive break with colonial Christianity, particularly the image of a white Christ. Christianity and its symbols must, therefore, reflect the condition of the suffering and exploitation of the world.

Urbaniak, Jakub. “Extending and Locating Jesus’s Body: Toward a Christology of Radical Embodiment.” Theological Studies 80, no. 4 (2019): 774–97. DOI: 10.1177/0040563919874520 URL: Link Access: Export Item

Urbaniak compares Gregersen’s deep incarnational Christology, as a universalising European Christology, with Maluleke’s black African Christology. He identifies two ways in which incarnation theologians ask important questions for African Christologies: they bridge the gap between the universal and particular, and they move from a cross-centred Christology of suffering to one that additionally emphasises resurrection. He concludes by identifying the cross as the locus of mystical reconciliation and prophetic resistance.

Urbaniak, Jakub. “What Makes Christology in Post-Apartheid South Africa Engaged and Prophetic? Comparative Study of Koopman and Maluleke.” In Theology and the (Post)Apartheid Condition: Genealogies and Future Directions, edited by Rian Venter, 125–55. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State, 2016. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Urbaniak compares the christological perspectives of Koopman and Maluleke—representing public and black theology, respectively—and assesses their christological conclusions based on their contextual engagement and prophetic potential. Comparing Koopman’s ‘global Reformed Jesus’ and Maluleke’s ‘African Jesus’, Urbaniak concludes that while Koopman’s Christology fails to meaningfully engage African contexts, Maluleke’s represents both an engaged and prophetic Christology for Africans today.

Reconstruction Christologies

The reconstruction trend began in the early 1990s following the fall of communism and the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa. In November 1991, during the symposium on the ‘Problems and Promises of the Church in Africa in the 1990s and Beyond’, convened in Mombasa, Kenya, the theme of ‘Theology of Reconstruction’ was launched. Some of the pioneers of this trend include Jesse Mugambi, Kä Mana, and Valentin Dedji, among others. For example, according to Mugambi, one of the originators and main proponents of the reconstruction trend, the key term in African Christian theology for the twenty-first century should be ‘reconstruction’. In his view, the core of the reconstruction trend is to be located in the spirit and work of ‘building up’ people and communities in Africa. The Congolese philosopher and theologian, Kä Mana, was another foremost theologian of reconstruction present at the symposium. In his celebrated work on this trend, Mana argues that the building of a new African society should not be based on the logic of market economy, but rather on the Christological-Resurrection-Event of Jesus Christ and the principles it entails (Mana 2002). These leading theologians in the field of reconstruction claimed the new trend would unveil a Christology that puts special emphasis on the social reconstruction of Africa. This emphasis would demand that the christological imagination of African Christians be taken seriously. It would also require a more concrete engagement with the ‘Christ-Event’, which is considered to be significant for offering a meaningful and relevant theological response to the real and complex social problems of Africa.

Gathogo, Julius. “Reconstructive Hermeneutics in African Christology.” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 71, no. 3 (April 10, 2015): 1–8. DOI: 10.4102/hts.v71i3.2660 Access: Export Item

For Gathogo, reconstructive Christology is the seventh trend in contemporary African Christology. This essay draws its theoretical framework from the works of Jesse Mugambi, Kä Mana, and Patrick Wachege, amongst other proponents of the reconstruction paradigm in African theology. Gathogo presents Christ as the ideal reconstructor who dismantles the old order of injustice and oppression and inaugurates a new one by his teachings and examples.

Mana, Kä. Christians and Churches of Africa: Salvation in Christ and Building a New African Society. Yaoundé and Akropong-Akuapen: Editions Clé and Regnum Africa, 2002. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Mana proposes a christological ethic based on the identity and work of Christ as ‘reconstructor’. Drawing on a number of biblical passages, Mana argues that Christ’s teachings and example portray him as the reconstructor whose life provides the blueprint for building a new African society. The work of rebuilding African society, Mana suggests, begins with the redemption of the ‘African imaginaire’ by Christ the reconstructor par excellence.

Mugambi, Jesse N. K. From Liberation to Reconstruction: African Christian Theology after the Cold War. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1995. Export Item

Mugambi explores how Christian theology could fulfil its role in the social reconstruction of Africa. He then proposes ‘reconstruction’ as the theological project for contemporary African Christian theology. Reconstruction, derived from the wisdom of Jesus Christ, captures what is the proper defining dynamic, method, language, and goal of theological exploration, which will contribute to building a more human and humane society in Africa and elsewhere.

Mugambi, Jesse N. K. Christian Theology and Social Reconstruction. Nairobi: Acton Publishers, 2003. Export Item

In this work, Mugambi further develops his line of thinking from his earlier works on reconstruction, namely that the social reconstruction of Africa is at the heart of theological and christological engagement on the continent. Social reconstruction is modelled on the biblical image of building up or ‘constructing’ the kingdom of God, a kingdom of justice, peace, and love for all people, after the example of Christ the reconstructor.

Grassroots Christologies

In the African Christian context, Christology is not simply the work of professional theologians; it is also the exercise of ordinary believers who strive daily to make sense of the person and actions of Jesus Christ in their context. These latter perceptions are referred to as grassroots Christologies, or in some circles as ‘popular Christologies’ and ‘lived Christologies’ (Stinton 2007). These are the Christologies of the people, the non-elite African Christians, individuals and communities of faith, living their experiences of Christ in the day-to-day realities and challenges of life (e.g., Donders 1985; Pénoukou 1991). They are expressed in the worship, prayers, hymns, preaching, and conversations of Christians and their leaders. This is to say that the grassroots Christologies, to a large extent, represent an oral narrative style, even though they may also be articulated in books and articles by academic theologians. Grassroots Christologies are often expressed in images such as healer, liberator, and king. In addition to offering a living understanding of the identity and work of Christ, grassroots Christologies also relate something of the realities that people face and aspirations they have. This means that some of the images through which Christ is proclaimed, worshipped, or invoked in prayers point to the concrete situations of people who are suffering from illness (Jesus as healer), victims of social injustice (liberator), or people longing for a servant-leader (king) who will bring them integral well-being or one who accompanies them in the journey of life (friend/brother). The importance of such deeply embedded grassroots Christologies provides insight into imagining Christology in Africa and elsewhere, both as an academic exercise and as the practice of working out its potential for human and cosmic flourishing.

Donders, Joseph G. Non-Bourgeois Theology: An African Experience of Jesus. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1985. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Donders, an American missionary to Kenya, describes grassroots Christologies as the proclamation of Jesus Christ by non-elite members of the church – the primary bearers of faith in Christ. This book aims at capturing the christological “symbolism, mood, experience, dreams, and vision of people as they are” (p. vii). In these lie the embodied experience of Jesus as a living reality and as one who is present and active amongst people.

Dube, Musa W. “Who Do You Say That I Am?” Feminist Theology 15, no. 3 (2007): 346–67. DOI: 10.1177/0966735006076171 URL: Link Access: Export Item

Dube draws on the painful experiences of women in many social contexts to provide an affective account of Jesus’ identity as liberator, healer, the one who empowers us, and the one who commissions us to become effective agents of liberation, healing, and empowerment in people’s lives. One noteworthy goal of Dube’s essay is the validation of lived experience in a particular social context and relating this to Jesus’ own identity.

Ezigbo, Victor I. “Grassroots Christologies of Contemporary African Christianity: A Case Study of Nigeria.” In Re-Imagining African Christologies: Conversing with the Interpretations and Appropriations of Jesus in Contemporary African Christianity, 103–42. Princeton Theological Monograph Series 132. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2010. Export Item

Nigerian theologian Ezigbo argues that the task of re-imagining African Christologies demands that critical attention be paid to the ways African Christians, both scholars and ordinary believers, speak about, worship, celebrate, and pray in Jesus’ name. Ezigbo asserts that in grassroots Christologies, Christ is held up mainly as a ‘problem solver’, observing this as a shortcoming. He therefore proposes a ‘Revealer Christology model’ for addressing this lacuna in grassroots Christologies.

Goergen, Donald J. “The Quest for the Christ of Africa.” African Christian Studies 17, no. 1 (2001): 5–41. URL: Link Access: Export Item

Goergen, a Dominican Missionary in East Africa, describes the dominant images of Christ among African theologians, pastors, and ordinary Christians. The images include Christ as ancestor, healer, liberator, and king. According to Goergen’s further analysis, these images emerge from within context-aware, praxis-oriented, socio-politically conscious theologies. As such, they promote and have the potential to foster a new African consciousness within Christianity.

Mouton, Elan, and Dirkie Smit. “Jesus in South Africa – Lost in Translation?” Journal of Reformed Theology 3 (2009): 247–73. DOI: 10.1163/187251609X12559402787155 Access: Export Item

The authors survey four dominant discourses about Jesus in contemporary South African society, namely Jesus in popular news and newspaper debates, in scholarship, in the spirituality of Christian believers, and in public opinion concerning social and political life. The authors question whether these developments betray Jesus’ identity and whether there are ways in which the figure and message of Jesus may be lost in these diverse forms of translation.

Onaiyekan, John. “Christological Trends in Contemporary African Theology.” In Constructive Christian Theology in Worldwide Church, 355–68. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1997. Export Item