Why study Christian history? Knowledge (or ignorance) of history impacts identity: “a past is vital for all of us—without it, like the amnesiac man, we cannot know who we are” and thus “what is the past of the African Christian” will remain a prime question for African theology (Walls 1978, 13).

Kwame Bediako notes that “history from a Christian perspective becomes a study in cultural identity in which Christ emerges as not only the answer to the quests of the past, including religious quests, but also as the effective interpreter and the integrating factor in all human enterprise” (1992, 33). Walls notes that “the urge to make Christianity a place to feel at home, rooted in a people’s culture, life and language, is of the heart of the gospel because it is a fundamental of the gospel that God takes us as we are, simply on grounds of what Christ has done” (1978, 11). Knowing the Christian past of Africa demonstrates that the Church both should and can be “a place to feel at home” (Welbourn and Ogot 1966) for Africans and also makes it impossible to credibly argue that Christianity is a European phenomenon or “a white man’s religion.”

African Christianity is considerably older than the English, French, Portuguese, and German languages. African Christianity had been established as an authentic African expression of the faith for centuries before the rise of Islam. In Egypt and North Africa, Christianity is as old as the New Testament, which makes mention of black African Christians. There are churches in sub-Saharan Africa with a continuous seventeen-hundred-year history (Walls 2005, 440). Indigenous African churches, such as the Coptic Church in Egypt, the Aksumite Church in what is now Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, and the Nubian Church in what is now Sudan, had the Scripture in their own languages and well-developed liturgies when my Celtic ancestors were still painting themselves blue and practicing human sacrifice. Firm documentary evidence speaks of indigenous Christian communities in the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa (reigned c. 1312-37) and archaeological evidence strongly suggests Christian presence in what are now Chad, Mali, and Nigeria in the 1400s and 1500s, before the Portuguese began to explore those areas in the so-called European ‘Age of Discovery.’ Authentically African Kongolese Christianity not only thrived but had a discernible impact on the course of the Christian story in North America. We should know, and celebrate, the stories of African Christianity. Unfortunately, traditional “standard” Church history texts have all but ignored the role of Africa and Africans in the Church, but this is starting to change.

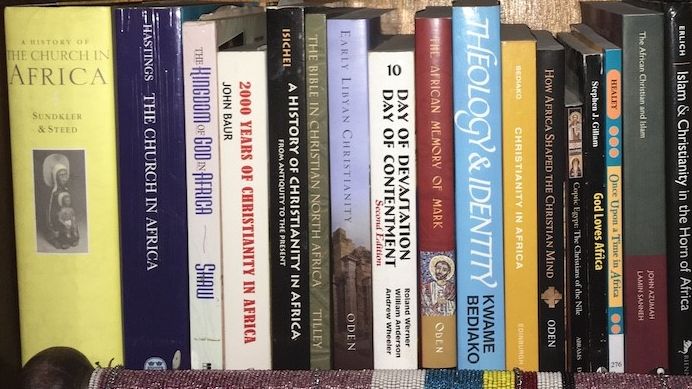

The most thorough one-volume histories of Christianity in Africa are Bengt Sundkler and Christopher Steed’s A History of the Church in Africa (2000), Adrian Hastings’s The Church in Africa 1450–1950 (1994), which is freely available here, and Mark Shaw and Wanjiru Gitau’s The Kingdom of God in Africa (2020). If someone only reads a single text on African Christian History, I always recommend Shaw and Gitau’s excellent volume, which is both the most accessible and the most well-rounded. In what follows I introduce a selection of key resources, highlighting their contribution to the history of African Christianity.

Abodunde, Ayodeji. A Heritage of Faith: A History of Christianity in Nigeria. 2nd edition. Lagos: Pierce Watershed, 2018. (826 pages). https://www.amazon.com/Heritage-Faith-History-Christianity-Nigeria/dp/9789442270.

Nigeria, with over 206 million people in 2020, is the most populous country in Africa. Of these, 95.3 million are Christians (Johnson & Zurlo 2023). As Andrew F. Walls observed on more than one occasion, a stereotypical contemporary Christian today is a Nigerian woman. If we don’t know the story of Christianity in Nigeria, we don’t know the state of Christianity in the world today. Thus, Abodunde’s magisterial work is most welcome. His story begins with the modern missionary movement, though in an appendix he discusses the period before the era of European colonization, including contact with the Portuguese in the 1400s. Though he seems unaware of the hints of Christianity in West Africa, including what is now Nigeria, before this time, his work for the time period covered is thorough.

Isichei, Elizabeth. A History of Christianity in Africa: From Antiquity to the Present. London: SPCK, 1995; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995; Lawrenceville, NJ: Africa World Press, 1995. (420 pages). https://www.eerdmans.com/9780802808431/a-history-of-christianity-in-africa/.

After its release, Isichei’s text became a standard text on the history of Christianity in Africa and, as such, was my introduction to the subject as a seminary student (when the book was new). Its coverage of African Christianity prior to the modern missionary movement is disappointingly scant: the first 1500 years of “North African Christianity in Antiquity” are glossed over in the first chapter, which offers only a few paragraphs each on Aksum and Nubia, while the second chapter introduces Christianity in Africa 1500–1800 yet neglects the stories of indigenous Coptic Christianity in Egypt during those years. Those who want more than a brief introduction to the history of African Christianity prior to 1800 will need to look elsewhere (e.g., Shaw and Gitau, 2020).

After she reaches the era of the modern missionary movement, there is little to complain of. Prof. Isichei is equally an excellent historian and an excellent narrator. She successfully emphasizes the crucial importance of African agency and initiative in the growth of Christianity in Africa, deliberately building on the work of Nigerian historians J. F. Ade Ajayi and E. A. Ayandele, while still acknowledging the role of Euro-American missionaries. Her coverage of different regions and different Christian movements is thorough, and her writing is engaging. Although this text is now dated, it remains important and my copy is shelved within easy reach. It is also freely accessible here.

Kalu, Ogbu U., ed. African Christianity: An African Story. Perspectives on Christianity Series 5, vol. 3. Pretoria: Department of Church History, University of Pretoria, 2005. Reprint Edition: Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2007. (509 pages). https://africaworldpressbooks.com/african-christianity-an-african-story-edited-by-ogbu-u-kalu/.

Professor Ogbu U. Kalu (1942–2009) was a pioneer among African historians of Christianity, whose key works include Christianity in West Africa: The Nigerian Story (1978), his edited volume The History of Christianity in West Africa (1980), which is freely available here, A Century and a Half of Presbyterian Witness in Nigeria, 1846–1996 (1996), The Embattled Gods: Christianization of Igboland, 1841–1999 (2004), and African Pentecostalism: An Introduction (2008), which is freely accessible here. He was also an early proponent of the study of World Christianity, and an astute theologian. This accessible edited volume, composed under his guidance, is freely available here and is a “must read” text for those interested in African Christianity. Kalu dedicated this volume to Andrew F. Walls and Brian Stanley, saying “many have bemoaned the collapse of Christian scholarship in Africa, you both have done something about it”; Kalu himself has also done something about it. Part One of this book, in seven chapters, is about “The Insertion of the Gospel.” Kalu starts with one chapter on African Church Historiography and another giving an overview of African Christianity. The next chapters cover “Early Christianity in North Africa” and “Christianity in Sudan and Ethiopia”, which serve to root contemporary Christianity in the ancient African past. Next come “Islamic Challenges in African Christianity”, “African Chaplains in Seventeenth Century West Africa”, and “Iberians and African Clergy in Southern Africa.” Part Two forms an ellipsis around two foci: “Missionary Presence and African Agency.” Jehu J. Hanciles begins with “White Abolitionists and Black Missionaries.” Other chapters focus on revivals and AICs. Part Three explores “New Dimensions of African Christian Initiatives,” starting from the period of the World Wars and progressing to the present. African Pentecostal/Charismatic Christianity, African theology, and the contribution of African women theologians are key themes.

Oden, Thomas C. How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind: Rediscovering the African Seedbed of Western Christianity. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2007. (204 pages). https://www.ivpress.com/how-africa-shaped-the-christian-mind.

More than anyone besides perhaps Andrew Walls (1928–2021) and Kwame Bediako (1945–2008), Thomas C. Oden (1931–2016) has helped Western readers become aware of the importance of Africa in the history of global Christianity. How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind (2007), which is freely accessible here, clearly demonstrates the debt that World Christianity as a whole, including Euro-American Christianity, owes to ancient African Christianity. Oden cogently and correctly situates theologians such as Antony, Athanasius, Augustine, Clement, Cyprian, Cyril, Donatus, Origen, Pachomius, and Tertullian as African. This book reveals that Christianity is authentically an African Traditional Religion (ATR), and arguably has been so longer than Bantu ATRs in many parts of Africa. How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind successfully corrects common misassumptions about the nature of the Christian movement.

Oden’s other key texts continue along this path. The African Memory of Mark (2011a) explores the African-Jewish — authentically Jewish yet authentically African — identity of John Mark, the apostle and evangelist from the African city of Cyrene (Libya). Though history does not inform us of the earliest beginnings of Christianity in Alexandria, uniform Church tradition confirms that the Church in Alexandria was eventually organized by St Mark. Early Libyan Christianity (2011b), which is freely accessible here, shows that there were vibrant African centres of Christianity in what are now Libya and Tunisia when the Christian community in Rome was primarily composed of Greek-speaking immigrants. The history of Christianity in Egypt and Tunisia is perhaps better known, as the church leaders of Alexandria (e.g., Clement, Origen, Athanasius) and Carthage (e.g., Tertullian, Cyprian; Augustine was also from the region) rose to greater fame, but the depth and breadth of Christianity in Libya was equally impressive from the days of the Apostles until the Islamic conquest. These three texts illuminate the ways in which “the classic mind of world Christian orthodoxy is significantly shaped by the North African imagination spawned indigenously of North African soil. The thought worlds following the genius of Origen, Augustine, Athanasius and Cyril bear the imprint of philosophical analyses, moral insights, discipline and scriptural interpretations that bloomed first in Egypt, Libya, Proconsular Africa and Numidia before they were consensually grasped elsewhere” (Oden 2011b, p. 274).

Shaw, Mark, and Wanjiru M Gitau. The Kingdom of God in Africa: A History of African Christianity. Revised and updated edition. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, 2020. (384 pages). https://langhamliterature.org/the-kingdom-of-god-in-africa.

This is a revision of Shaw’s earlier work, The Kingdom of God in Africa: A Short History of African Christianity (1996) – freely accessible here – which I first used in 2010 while preparing to teach a Church History course in Turkana Land in northwest Kenya. More than any other book, The Kingdom of God in Africa (1996) has shaped both my historiography and my narrative approach to teaching Christian history. As excellent (and as influential on me) as the first edition was, the second edition is an improvement. The authors look at the narratives of Christian history in Africa through the lenses of different understandings of the kingdom of God. Part one, “The Imperial Rule of God”, examines the stories of Christianity in Egypt and North Africa from their beginnings through 640 and in Ethiopia and Nubia through 600. Next, “The Clash of Kingdoms” explores Medieval African Christianity, 600–1700, including the collapse of Christian Nubia, the survival of Christian Ethiopia, and the reintroduction of Christianity to sub-Saharan Africa outside of Ethiopia through contact with Europeans. “The Reign of Christ” has four chapters covering the abolition movement and Christianity in West, Southern, and East Africa in the 1700s and 1800s. The final part, “The Kingdom on Earth,” explores African Christianity from 1900 to the present.

The authors acknowledge that while writing “uncritically about Christian history is a great error,” writing “without sympathy is a greater error” (p. 5). Moving beyond “missionary historiography,” “nationalist historiography,” and “ecumenical historiography,” which often fail to be sufficiently critical, Shaw and Gitau write from a World Christianity perspective, following in the footsteps of scholars such as Lamin Sanneh and Andrew F. Walls. Looking back to the days of Speratus and his eleven Scillitan companions who were martyred with him for their shared faith on July 17, 180 in Carthage (pp. 341–42) and looking forward with hope to the future of Christianity on the continent, the authors argue that “African evangelical theology can provide the foundation for a critique of messianic nationalism with its pretensions about building the kingdom on earth. Such an eschatology can be a useful reminder that all human structures are fallen and limited. A rediscovery of the lordship of the risen and returning Christ of orthodoxy over the political and intellectual Caesars of our time may be a force for the renewal of African Christianity in the third millennium” (p. 333).

Sundkler, Bengt and Christopher Steed. A History of the Church in Africa. Studia Missionalia Upsaliensia 74. Cambridge University Press, 2000. (1232 pages).

Hardcopies are sadly out-of-print and used copies are hard-to-find, but digital access is available via CambridgeCore.

Bengt Sundkler (1909–1995) was the doyen of Christian History in Africa for his generation, starting with his seminal Bantu Prophets of South Africa (1948), which is freely accessible here. Those were followed by Zulu Zion and Some Swazi Zionists (1976), which is freely available here, and Bara Bukoba: Church and Community in Tanzania (1974 in Swedish, 1980 in English, and 1990 in kiSwahili), which is freely accessible here. His magnum opus, however, is this splendid and comprehensive volume. He worked on researching and writing it for over 15 years before his passing; Christopher Steed polished the manuscript for publication after his death. Sundkler recognized that church history needed to be interpreted specifically “from a distinct African perspective,” not least because across the continent “the Christian message” has always been “largely transmitted by African initiative” (p. 2). The first part of the volume, “The First Fourteen Hundred Years” contains only one chapter, “The Beginnings,” of 35 pages. While this is lamentably brief, it is as thorough an introduction as one could hope for in so few pages. The second section is able to go into more detail, as its single chapter covers about three and a half centuries, 1415–1787. The rest of the volume is encyclopedic in scope. Part three, “The Long Nineteenth Century,” offers nine chapters and covers every region of Africa. The 39 years covered in Part 4, “The Colonial Experience 1920–1959,” are comprehensively dealt with in seven chapters. Part 5 covers “Independent Africa 1960–92” in seven more chapters. That the majority of book covers only the two centuries from 1790 to 1990 is excusable, as it is during that time frame that “Christian influence” has made its “decisive contribution to the Christian culture and life in sub-Saharan Africa” (1039). The book is written in an accessible style for those who set aside the time to read it cover-to-cover. It is also invaluable as a reference volume; I keep my copy on the shelves above my desk within easy reach.

Werner, Roland, William Anderson, and Andrew Wheeler. Day of Devastation, Day of Contentment: The History of the Sudanese Church across 2000 Years. 2nd edition. Faith in Sudan 10. Nairobi: Paulines, 2010. (472 pages). https://shop.paulinesafrica.org/product/Day-of-Devastation--Day-of-Contentment---The-History-of-the-Sudanese-Church-across-2000--years.

If hardcopies are out-of-print, a Kindle edition is available at Amazon.

The first five chapters of this excellent but hard-to-find volume cover the thousand-year history of Nubian Christianity: “The Early Nubian Church and Its Faith.” We know from Luke of a Nubian convert to Christ in the first century: the “Ethiopian Eunuch” of Acts was a government official of the ruling queen of the Nubian kingdom of Meroë. But as this kingdom collapsed around 300, we don’t know how Christianity may or may not have fared there. The authors therefore pick up with the slow Christianization of Nubia in the 300s, the conversion of Silko, the first Nubian king to embrace Christianity (sometime before 450), and the official conversion of the three Nubian kingdoms that succeeded Meroë in the 500s. This section is important because it shows how deeply rooted Christianity was in sub-Saharan Africa even from the patristic period (the story of Ethiopian Christianity is important for the same reason): Christianity is an authentic indigenous African religion. Eventually, Nubian Christian civilization was overrun, but only after a glorious history. The next three sections of the book cover the partial re-conversion of the Sudan and the growth of Sudanese Christianity in the 1800s and 1900s. The book contains helpful maps and color plates of ancient Nubian Christian ruins and iconography, as well as photographs of modern Sudanese Christians. Note that the book was published prior to South Sudan’s independence in 2011, and tells the stories of Christianity in both Sudan and South Sudan.

Joshua Robert Barron is a missionary and theological educator from the USA. He has teaching experience in India, South Africa, the United States, and Kenya, where he has lived with his family since 2007. He has written several articles and chapters, including “Connections and Collaborations among the Nubian, Coptic, and Ethiopian Churches,” chapter 6 in Globalizing Linkages: The Intermingling Story of Christianity in Africa, edited by Wanjiru M. Gitau and Mark A. Lamport, 91–107, The Global Story of Christianity: History, Context, and Communities 3, (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, forthcoming in 2024). He regularly contributes to the Collaborative Bibliography of African Theology and maintains other scholarly bibliographies related to African Christianity and World Christianity on his Academia.edu page. He is currently on staff with the Association for Christian Theological Education in Africa (ACTEA), and is a founding and managing editor of ACTEA’s new journal, African Christian Theology.

Photo Credit: Joshua Robert Barron

Other Sources Cited

Bediako, Kwame. “The relevance of a Christian approach to culture in Africa.” In Christian Education in the African Context, edited by International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education, 24–35. Proceedings of the African Regional Conference of the International Association for the Promotion of Christian Higher Education (IAPCHE), 4–9 March 1991, Harare, Zimbabwe. Grand Rapids, MI: IAPCHE, 1992; Potschefstroom: PU for CHE, 1992.

Johnson, Todd M., and Gina A. Zurlo, eds. World Christian Encyclopedia Online. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2023. Articles: “Africa,” accessed November 2023, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2666-6855_WCEO_COM_01AFR, and “Nigeria,” accessed November 2023, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2666-6855_WCEO_COM_02NGA.

Walls, Andrew F. “Africa and Christian Identity.” Mission Focus 6 (1978): 11–13.

———. “The Cost of Discipleship: The Witness of the African Church.” Word & World 25, no. 4 (2005): 433–443.

Welbourn, Frederick Burkewood, and Bethwell A. Ogot. A Place to Feel at Home: A Study of Two Independent Churches in Western Kenya. Oxford University Press, 1966.